Sir Hubert Wilkins

Detroit's expedition to the Arctic

1926 - Detroit News and Carl Ben Eielson

1927 - Detroit News-Wilkins Artic Expedition

1928 April - Wilkins and Eielson finally flew over the polar sea, landing successfully in Spitzbergen

Detroit's expedition to the Arctic

1926 - Detroit News and Carl Ben Eielson

1927 - Detroit News-Wilkins Artic Expedition

1928 April - Wilkins and Eielson finally flew over the polar sea, landing successfully in Spitzbergen

The matter of equipment was ostensibly left to the Select Committee of Detroit Engineers. But long before they had come to a decision, I had ordered two Fokker monoplanes; one seventy-two foot wing to be fitted with three Wright Whirlwind engines, and one sixty-three foot wing, which was already fitted with a special Liberty engine. Wilkins, Captain George. Flying The Arctic . Daniel J Wood. Kindle Edition.

Eielson had made provisional arrangements for the use of the hangar and field belonging to the Fairbanks Airplane Corporation, Wilkins, Captain George. Flying The Arctic . Daniel J Wood. Kindle Edition.

In less than a week the field was ready. Considering our bad luck with the three-engine machine, we decided to test the single-engine machine first. It had been christened the Alaskan and had dual controls.

We had been in the air about forty minutes, sufficiently long to get acquainted with the feel of the ship, so I asked Eielson to land. I was aghast when, just before reaching the end of the runway, Eielson almost closed the throttle and the machine immediately stalled.

We had considered the Fokker landing gear weak for the maximum load we hoped to carry. It was sufficiently strong for all ordinary purposes, but no landing gear ever made would have stood the crash of our three-ton machine as it fell to the frozen ground. One side of the landing gear crumpled. Then the other gave way. We slithered along the ground for a few feet, slewed into the snow bank and started to turn turtle. Seated as we were between an eight hundred gallon gas tank and a six hundred pound engine, I was badly scared. We could see the frame of the engine crumpling and being forced back upon us. It was an uncanny feeling. The tail of the machine was rising rapidly, but it seemed a slow movement to us; we could sense and see every move. Up and up it went until the machine was almost vertical. Parts of the engine frame stuck through its firewall into our cockpit. In a fraction of a second the machine would fall on its back and we would probably be as flat as pancakes. But no! It quivered in the balance for a moment, then slowly settled back with its tail high in the air. Neither Lanphier nor myself was injured in the slightest. It was my second escape in twenty-four hours. Wilkins, Captain George. Flying The Arctic . Daniel J Wood. Kindle Edition.

Well, we climbed out of the cockpit to examine the damage. The landing gear was almost a complete write– off, as was the central engine mount. We could manage to fix up the Alaskan with the spare material we had brought with us, but it would take weeks and weeks to get the material and repair the Detroiter.

After three weeks the Alaskan was ready. We would take no avoidable risks, nor could we spare the time for trials and the tests we had planned. We should load the Alaskan, and with Eielson as the pilot, take off and fly to Barrow, endeavoring to do something before there was a chance of another accident.

CHAPTER IV WINGS OF WOOD

We could afford no further delay and on March thirty-first, with a load of about three thousand pounds in the machine, Eielson climbed in and took the controls. I seated myself beside him and we took off. The Alaskan flew almost, but not quite as well as before. We had a load much heavier than had ever been carried in a plane of that size with a Liberty engine.

Since the crash, we had installed the new engine which, while a beautiful piece of workmanship specially selected at the Ford Factory and presented to us by Henry Ford, was not as well tuned-up as the one first on the machine. The engine originally used had been built by Johnson of New York especially for racing purposes, and Johnson himself had assured me there was not a better Liberty engine in the United States. I believe he was right.

Neither was the second propeller as efficient. We had at first used a perfect Curtis Reed twisted metal propeller, but after the crash, we had to use an old club propeller that had been thrown in with our equipment as an afterthought. A new wooden propeller ordered from Hamilton’s had not arrived. But the Alaskan still handled well. We climbed steadily and steadily upwards, knowing we would have to reach five thousand feet to cross the first range of hills with safety. We thought that an altitude of six thousand feet would see us through because the peaks of the Endicott Range barring our course were shown on the very latest maps procurable as five thousand feet. We had secured these maps with the assistance of the United States Geological Survey.

We had filled the radiator of the Liberty engine with a mixture of eighty percent water, fifteen percent alcohol and five percent glycerin, so we had no occasion to empty the radiator before a starting even at the lowest temperatures experienced.

The three-engined machine, which had been that day christened the “Detroiter”

Single Engine Fokker called the “Alaskan”

Wilkins, Captain George. Flying The Arctic . Daniel J Wood. Kindle Edition.

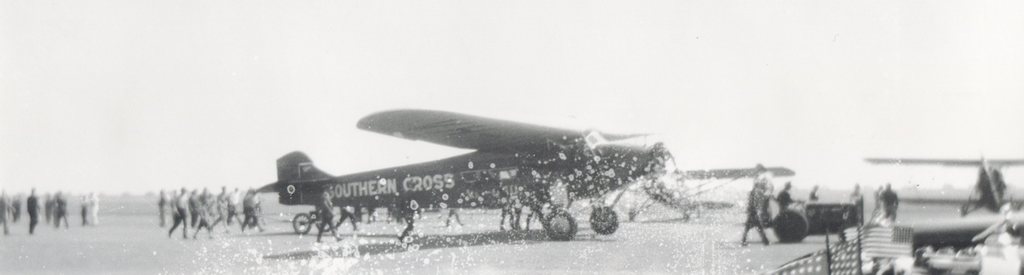

It was the flight which made ‘The Southern Cross’ famous. While in America Sir Charles Kingsford Smith (Smithy) purchased a three engine Fokker F.VIIb second hand from fellow Australian and Arctic explorer Sir Hubert Wilkins without engines. With new engines installed he then set out in the ‘Old Bus’ (as he called it) to cross the Pacific along with Charles Ulm (co-pilot) and Americans Harry Lyon (navigator) and Jim Warner (radio operator) .

Departing Oakland California on 31 May 1928 they flew 11,585 kilometres (mostly over water) via Hawaii and Suva to Brisbane’s Eagle Farm aerodrome in a flying time of 83 hours and 50 minutes. The flight encountered severe storms enroute which only added to the danger of flying and navigating over the ocean. Flying in an open cockpit was so noisy that for the crew to communicate messages and course directions needed to be written down. The Southern Cross, Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith and his crew are seen here arriving in Brisbane 9 June 1928 along with some of the crowd of 15,000 people who had gathered to witness their arrival as the first to have flown the Pacific.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia vimeo.com - NFSA - Conquest of the Pacific