Cold Weather Engine Starting

Aero Digest - December, 1926 - Page 440

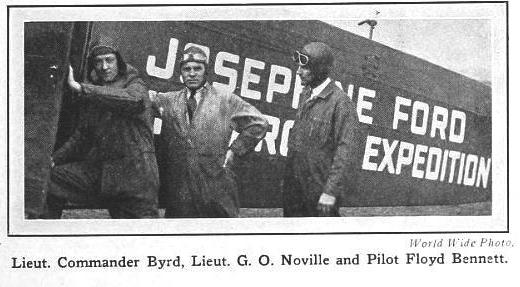

By G. 0. Noville

Lubrication Engineer,

Byrd Arctic Expedition

Of the many problems that had to be solved to insure the success of the flight of the Byrd Arctic Expedition to the North Pole one of the most important was that of starting and lubricating the three Wright J4 air-cooled engines in the low temperatures encountered.

Consideration was given to various light-bodied oils which would remain fluid at low temperatures and which would permit of fairly easy starting under such conditions, but there were objectionable features to their use. Under full load operation the lighter-bodied oils would not seal the piston rings and maintain the high compression pressure in the combustion chambers necessary to secure full power output from the engines.

Leakage past the rings could be expected, which would result not only in a loss of power and higher fuel and oil consumption (Items that had to be carefully avoided) but also would cause excessive dilution of the oil by this fuel and reduce its lubricating value. Such conditions seriously affect the operation of the engines.

Another factor which opposed the use of the lighter-bodied oils was the high internal temperatures under which the oil would have to work when the engines were in operation. Although the outside air temperatures at starting and during the flying were extremely low—about 10 deg. below zero on the ground, and 32 deg. below zero in the propeller air stream at 3,000 feet altitude—the air-cooled cylinders were so protected by an aluminum cowling that shortly after taking off the engines reached approximately their normal operating temperatures internally. The oil temperatures during the flight were all within a reasonable range of normal. As all oils thin out under heat to an extent dependent upon the character of the oil, it was decided that the lighter-bodied oils would be impractical as long continued flight would probably reduce their body to a point where lubrication might be impaired.

It was decided to use the oil best adapted to the lubrication of the engine under operating conditions, and a method was devised whereby easy starting might be accomplished in low temperatures. The plan adopted was to use a method of heating the engines and to start with preheated oil.

The gradual heating of the engines externally before they were fired internally reduced the danger of too rapid expansion of the metal due to change in temperature from that of the cold air to the temperatures developed by operation. This procedure further insured positive action of the engine cam followers which, if supplied with a cold viscous lubricant, would probably cause a lagging or sticking of the valves and sluggish interrupted action of the engine generally.

Preheating the oil was a simple matter and the same procedure was adopted as had previously been employed in Alaska, Greenland and Labrador on the U. S. Army Round-the-World Flight and on other flights where low temperatures were encountered. Gargoyle Mobiloil "B" was supplied in five gallon cans by the Vacuum Oil Company and a requisite number of these were placed in a circle around an open wood fire. The cans were rotated so that the contents became thoroughly heated.

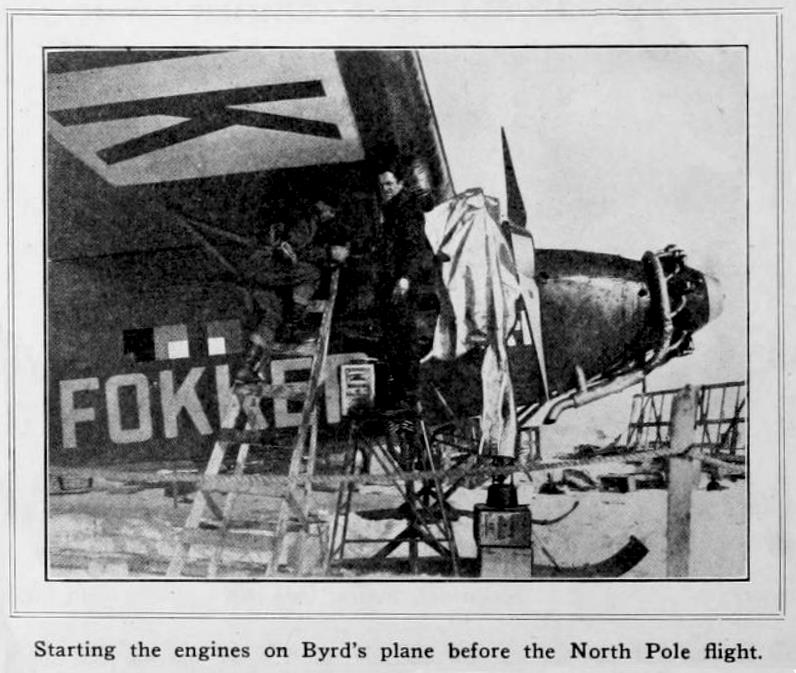

A device was arranged to completely hood the engines and apply a steady flow of hot air which would circulate around the engines and pass on to warm the oil tanks and oil lines enclosed in the engine nacelles.

This heating device was made of eight-ounce fire-proofed canvas. Hoods were designed to fit securely over each engine. From the bottom of these hoods, flues or ducts about a foot in diameter were carried to within a few feet of the ground. Covering the engines and applying the heating units is only a matter of a few minute's work. Three gasoline pressure torches were placed at each flue, starting a flow of heated air through the hoods, warming the exposed metal parts of the engines. After circulating around the engines the hot air escaped through vents and followed the back cowling openings into the engine nacelles where it heated the oil tanks, oil feed lines and discharge lines.

At ten degrees below zero, fifteen minutes after the heating operation was begun the engines were perfectly free and could be turned easily by hand and were started without any difficulty on the first turn of the crank. Starting was accomplished with greater ease than is usually the case under summer temperatures. The oil immediately built up a normal oil pressure, instead of the excessive and dangerous pressures encountered when the engines are started with cold oil even at favorable air temperatures.

This method of preheating the oil and engine is neither difficult nor dangerous. There are a few precautions which must be observed, however. The gasoline line should be shut off at the tank, and the carburetor and line drained before the hood is applied. A fire extinguisher should be on hand.

The conditions under which this starting was accomplished were, of course, abnormal, but this method of starting, permitting the use of the most efficient oil to meet the wide-open-throttle operating conditions, proved to be so simple and so practical that its description will interest those who may be confronted with such lubricating problems.