Adventures of an Alaskan biplane

By Les and Janet Kares

The resolute Bush Pilots and Mechanics flying their small open cockpit planes into Alaska's remote wilderness lands, were responsible for ushering in the air age of Alaska and led the way for the growth of that state.

Flew of the original early planes of the late 1920's survive - - - here is the story of one, long lost and all but forgotten, that returned to fly again.

During the summer of 1968, while still living near Seattle, Washington, I was half heartedly looking for another aircraft to rebuild, and inadvertently became the recipient of the remains of an aircraft so deteriorated that it was difficult to guess its origins, there being no clues of any kind on the frame, though it did appear that someone had recently removed a data plate from near the rear cockpit. That it had been a biplane was the only thing certain. It was one of the worst piles of rotting wood spars and ribs and rusting tubing I had ever seen and wanted nothing to do with the mess at all, but took it since I didn't want the person making the offer to think that I was unappreciative of his gesture, although I also realized that had he felt it was worth anything he would have kept it himself. Antique builders don't part with anything unless it's absolute junk, which this was. I honestly intended to haul it out to the dump after a few weeks, but fortunately I received some information about the plane that piqued my curiosity and I delayed my earlier intention. After recovery of the data (name) plate, I realized the ship was a rare early model Stearman, model C2B, and continued investigation brought forth more interesting details of its useful life in Alaska. It became apparent that no matter how great an amount of work I was facing, I should give serious consideration to restoring the plane.

As restoration continued over the years, new facts, or clarification of old facts, developed and the following story covers some of the more interesting highlights of the history of Stearman C2B, NC5415.

It is a risky business to write such a history while some of the people who were a part of it are still living. Information from some of those directly involved has never been forthcoming, concerning some segments of the plane's history, so gaps are inevitable, but the facts about the main events covered are well documented.

On April 11, 1928, number 21, of what was to become a long and proud heritage of Stearman aircraft, numbering over 10,000, rolled out of the small factory in Wichita, Kansas and became finally, the oldest flying survivor. Stearman, Model C2B, Registration number NC5415 was built in the classic biplane configuration of that era.

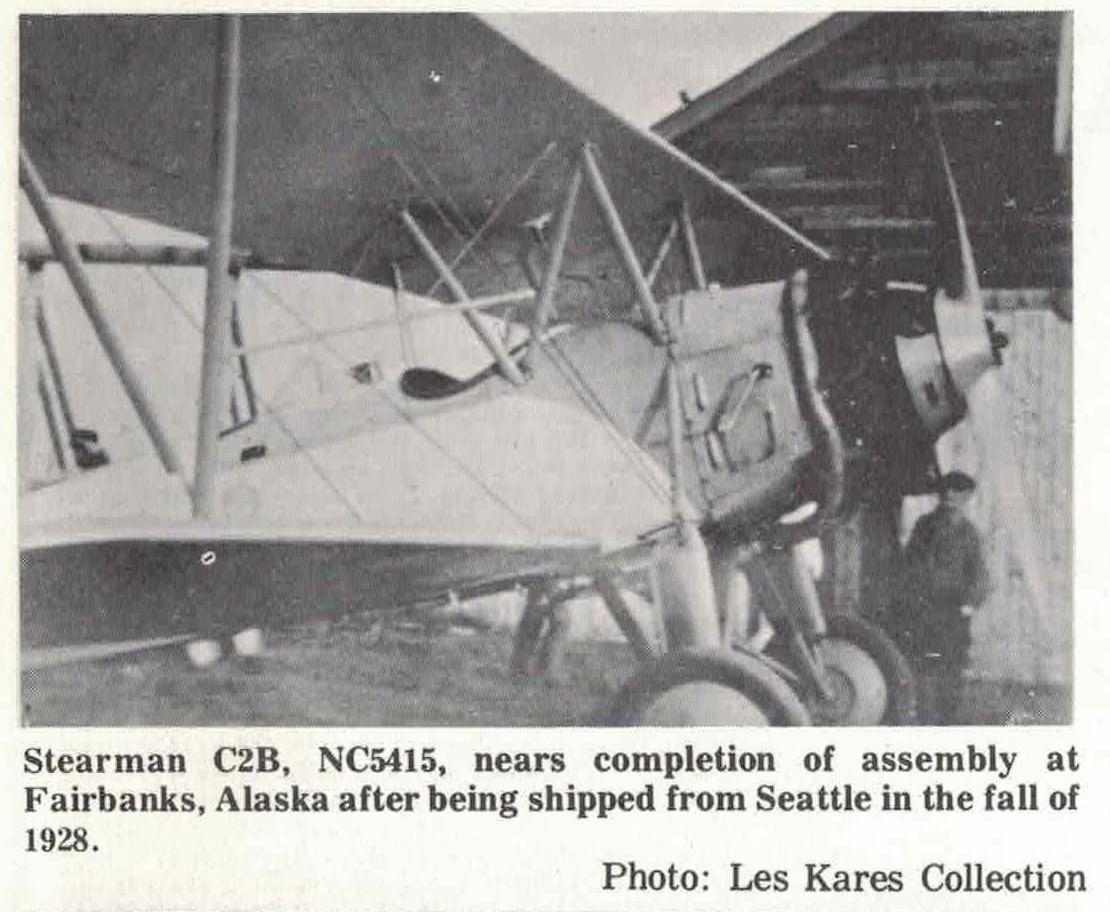

The disassembled plane was shipped to Fairbanks in the fall of 1928, and after reassembly was test flown by a pilot named Crawford and then began an adventurous career with Alaska's pioneer Bush Pilots encompassing exploits of bravery, fearlessness, fortitude and derring-do.

The plane's gallant career shortly received the first of many temporary setbacks when in April of 1929, it lay a wrecked heap on snow covered Walker Lake, 260 miles northwest of Fairbanks because the pilot had attempted to land in deep snow while the plane was equipped with wheels.

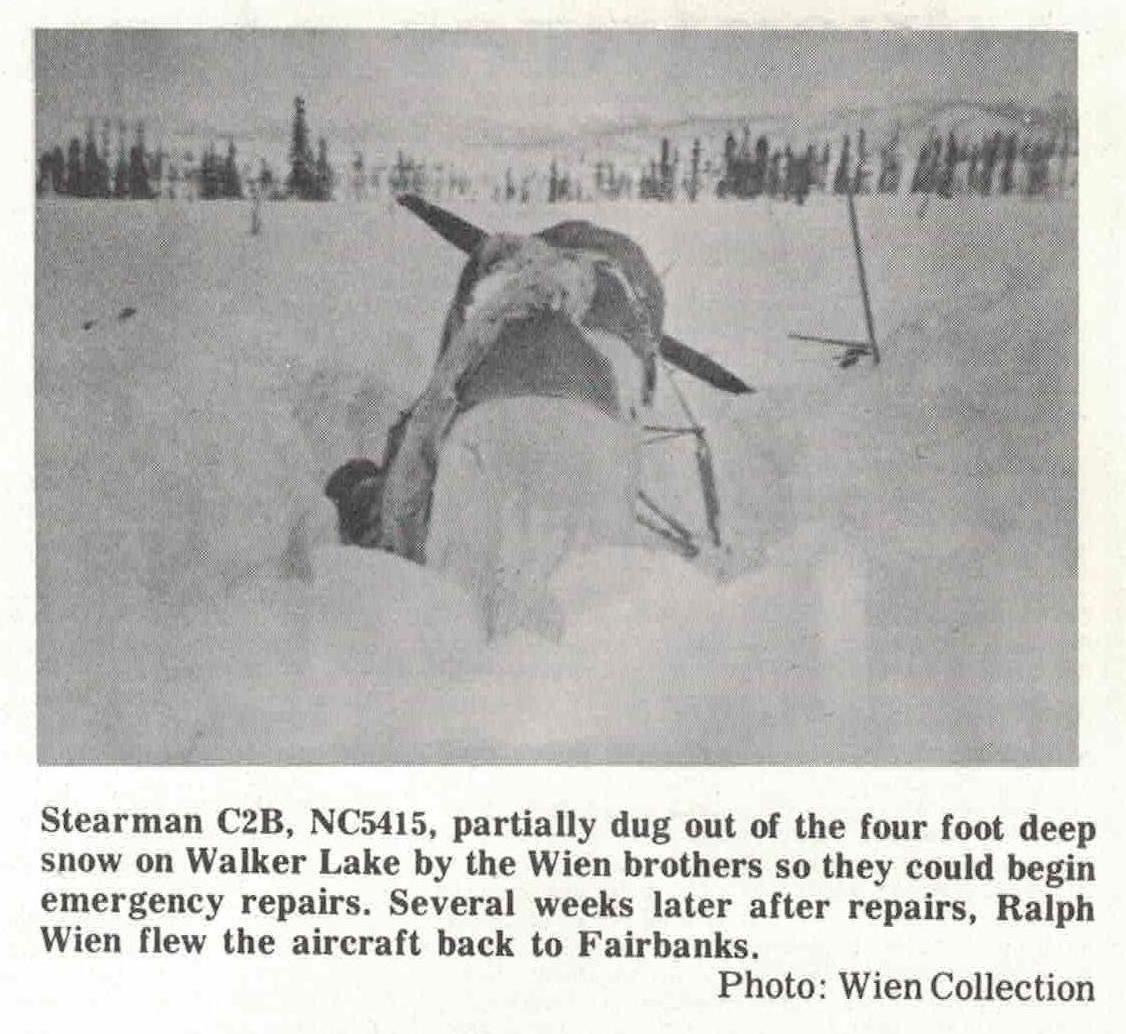

This writer, while still living near Seattle, had the privilege of becoming acquainted with the late Noel Wien (considered by...many to be the father of Alaska Bush Flying), and enjoyed Noel's account of how he purchased the Stearman wreck sight unseen and retrieved it. He and his brothers Fritz and Ralph, and mechanic, Earl Borland made the journey across the deep snow, dug the wreck out of four foot deep drifts, and over a period of several weeks rebuilt wing sections and made other emergency repairs. Skis, of course, replaced the useless wheels, Noel also related how he made the first test flight and almost ended. up in a second crash landing, since, being unfamiliar with the aileron rigging, they had rigged the controls backwards. On the takeoff run Noel said he realized the problem almost immediately, so was able to compensate and made a successful landing without causing any further damage. After proper rerigging, Ralph flew the plane back to Fairbanks where repairs were completed.

Along with other ships, the Stearman was utilized in the Wien air operations during the summer, but after a few months, Noel decided to sell his planes to a new young company, Alaskan Airways, founded by the noted Alaskan pilot Carl Ben Eielson. Eielson had become world famous after piloting Sir Hubert Wilkins on several Arctic and Antarctic expeditions, including their flight over the North Pole to Spitzbergen Norway. Other young pilots joining Alaskan Airways and who would soon become famous in Alaskan aviation history were Joe Crosson and a young but eager pilot named Harold Gillam who was still learning to fly. Gillam would soon figure with Stearman C2B in an episode fraught with tragedy and danger.

This writer is also fortunate to have the opportunity of corresponding with Mr. Robert Gleason, a pioneer in marine and aviation radio communication and author of the book "Icebound In The Siberian Arctic" which details much of the following.

An adventure, of little interest at the time, to other than those directly involved, had its beginning in the summer of 1929 when a small, but sturdy merchant sailing ship, the Nanuk (Nanuk is the Eskimo word for Polar Bear), left Seattle for a fur trading venture to the remote coastal villages of Arctic Siberia. After several near-disasters, the Nanuk's most remote destination, the village of Nizhekolymak on the Kolyma River in Siberia, was finally reached on August 23rd, 1929. In a desperate attempt to beat the winter freeze up, the crew hurriedly off-loaded the supplies for the village and taking on the cargo of furs, headed the little ship out on its treacherous eastbound trip back through the ever present ice pack of the Siberian Arctic.... They would not make it in time.

On October 4, 1929, word was sent out by the young radio operator, Bob Gleason, aboard the Nanuk, that the ship was caught in the frozen ice pack, and would have to winter near North Cape, Siberia, two hundred miles north of the Arctic Circle, and 500 miles northwest of Nome, Alaska. The cargo of furs had a 1929 value of over a million dollars, and with falling American prices, Mr. Swenson, the owner of the Nanuk and cargo, was naturally anxious to get the furs to the American market as soon as possible, as well as remove most of the crew members. By use of the ship radio, Swenson who was aboard the Nanuk, was able to arrange a contract with Ben Eielson and the newly founded Alaskan Airways to do the almost impossible job of flying the crew and furs to the Alaska mainland. Eielson was well aware of the risks involved but felt that a major contract such as this would help get the new company off to a healthy start.

For such an airlift in the dead of the Arctic winter, Eielson used two of the airplanes, a closed cabin Stinson Detroiter and the larger all metal Hamilton, that he had acquired from Noel Wien. These two aircraft with little difficulty made the first trip from Teller to the Nanuk on Oct. 29th, bringing back several crew members and a small amount of fur. In the Hamilton, Ben Eielson had as his riding mechanic and co-pilot, Earl Borland who had some months before helped with the repair of Stearman NC5415.

Snow, fog, and generally ugly weather delayed the start of the second trip to the Nanuk, but finally, on Nov. 9th, in spite of marginal conditions the two planes again headed across the Bering Strait. The Stinson soon returned, the pilot reporting heavy fog, but Eielson and Borland in the Hamilton did not return to Teller, nor did they reach the Nanuk. The bush pilots of the day often landed to wait out the weather, but by the middle of the month and after the weather had cleared for several days, genuine concern was felt when the two pilots did not show up anywhere.

The many friends of the pair began marshalling forces for a search, and an especially close friend, Joe Crosson, left Fairbanks for Nome and Teller in his open cockpit Waco biplane almost immediately.

The fledgling pilot, Harold Gillam, (some stories say he didn't yet have his pilots license) prevailed on the remaining Airway management in Fairbanks to let him join the search, so a couple of days later he, too, flew to Nome. His plane was Stearman C2B, NC5415. One story relates that although reluctant, Crosson finally agreed that Gillam could participate as long as he kept in sight of Crosson at all times.

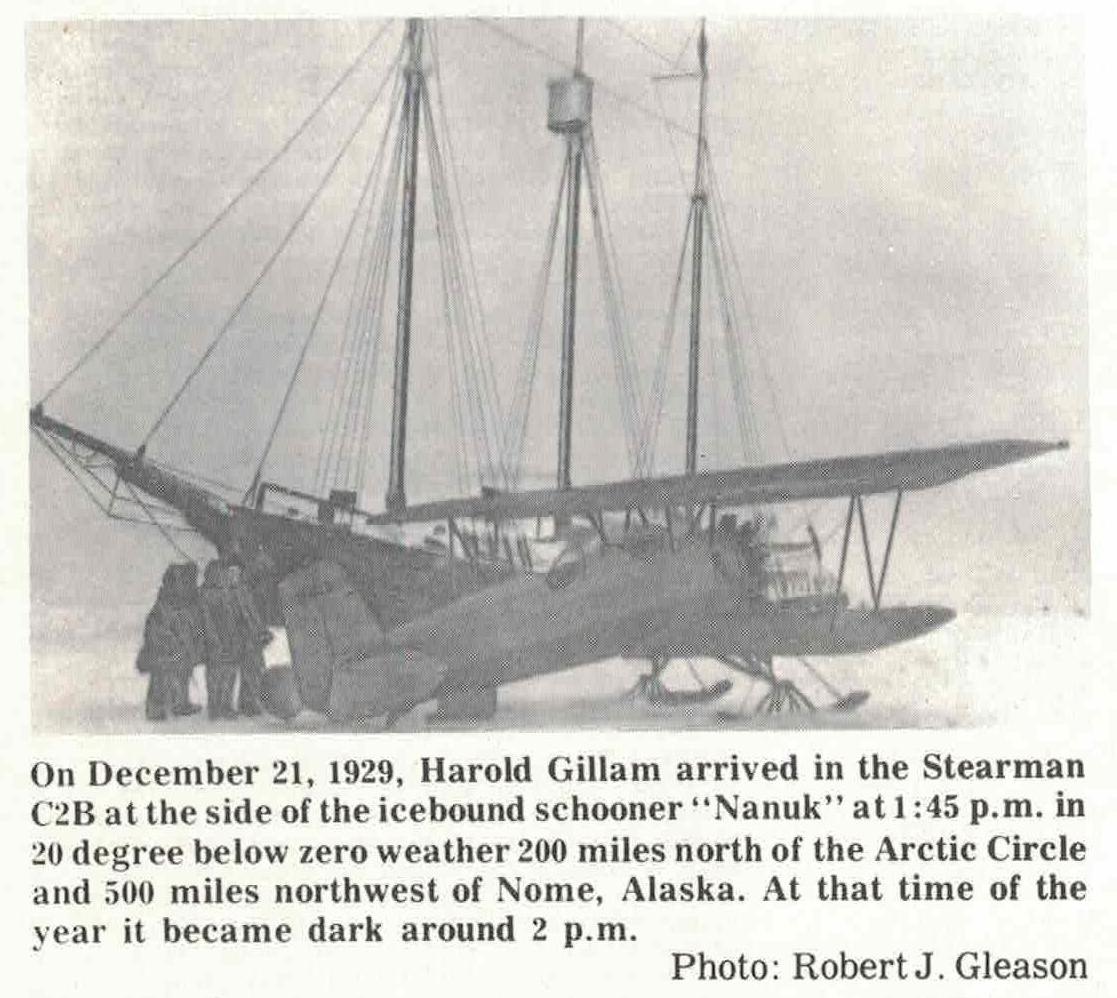

With temperatures ranging as much as forty below zero, storm after storm raged through the area preventing anyone from getting across the strait, although as many as four planes were trying. On Dec. 20th, Bob Gleason reported the weather was fair at the Nanuk, and although it was still marginal at Teller, Crosson and Gillam once more headed across the open water of Bering Strait. This time they did not return to Teller. Gleason and others aboard the Nanuk, knowing the planes were on their way, lit oil drum fires to mark the boundaries of a small landing area on the icepack near the ship. They kept the fires burning until long after dark unaware that Crosson and Gillam after crossing the strait and heading up the coast of Siberia had run into impassable flying conditions and had landed by an Eskimo village near Kolyuchin Bay to spend the night. Once again the crew of the Nanuk could only wait and hope that the pilots were safe.

The following morning Crosson and Gillam took off into gray skies, heading up the coast and had not gone far before the fog and low clouds separated the two fliers. Crosson, feeling that Gillam, a relatively inexperienced pilot, would return to the village, went back himself only to find that Gillam had apparantly continued on. Now Crosson feared there might be another lost pilot to search for. Gillam did continue on, cautiously following the ragged coastline, flying in and out of the blinding snowstorms. He later admitted flying the Stearman into a gradually rising hill at which point the skiis made contact and bounced him back in the air.

That same morning the crew of the Nanuk was up early searching the eastern sky hoping for some sight of the small planes. As the hours wore on past noon, concern grew because that far north, on this, the shortest day of the year, it would be full dark by two in the afternoon. The temperature was minus 20 degrees. Finally, a little before 1:45 in the afternoon a drone was heard in the eastern sky and a single plane approached, circled and landed. The small Stearman taxied up to the Nanuk and the pilot announced, "I'm Harold Gillam". Gillam had flown the small ill equipped biplane almost 500 miles through weather conditions that even today's modern planes would have difficulty traversing. In 1929 those were the modern planes and with buddies in trouble, little thought was given to the idea that it couldn't, or shouldn't be done. Crosson did arrive the next day without trouble, and although he was somewhat disturbed at Gillam's actions of the day before, was nonetheless delighted to see that he had arrived safely.

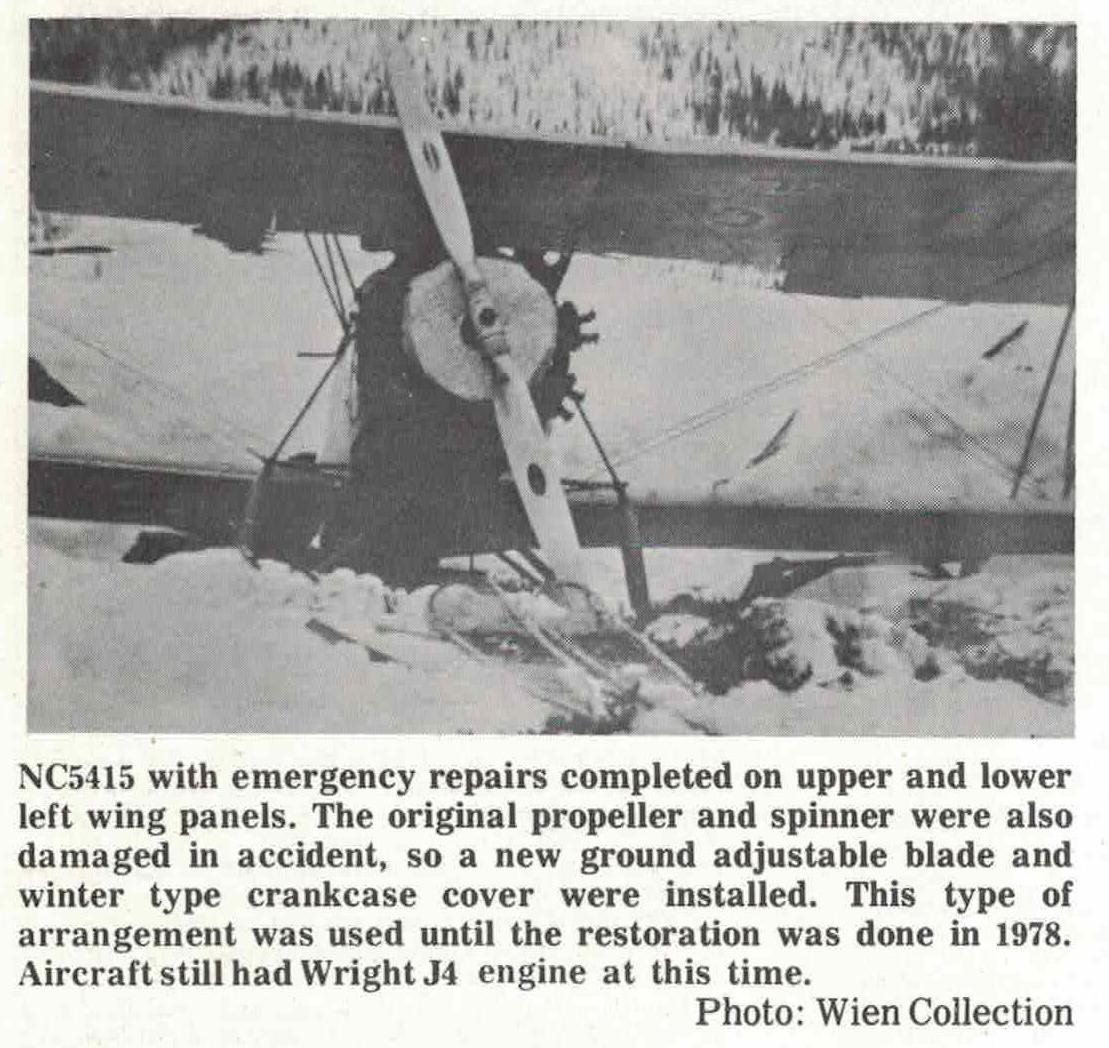

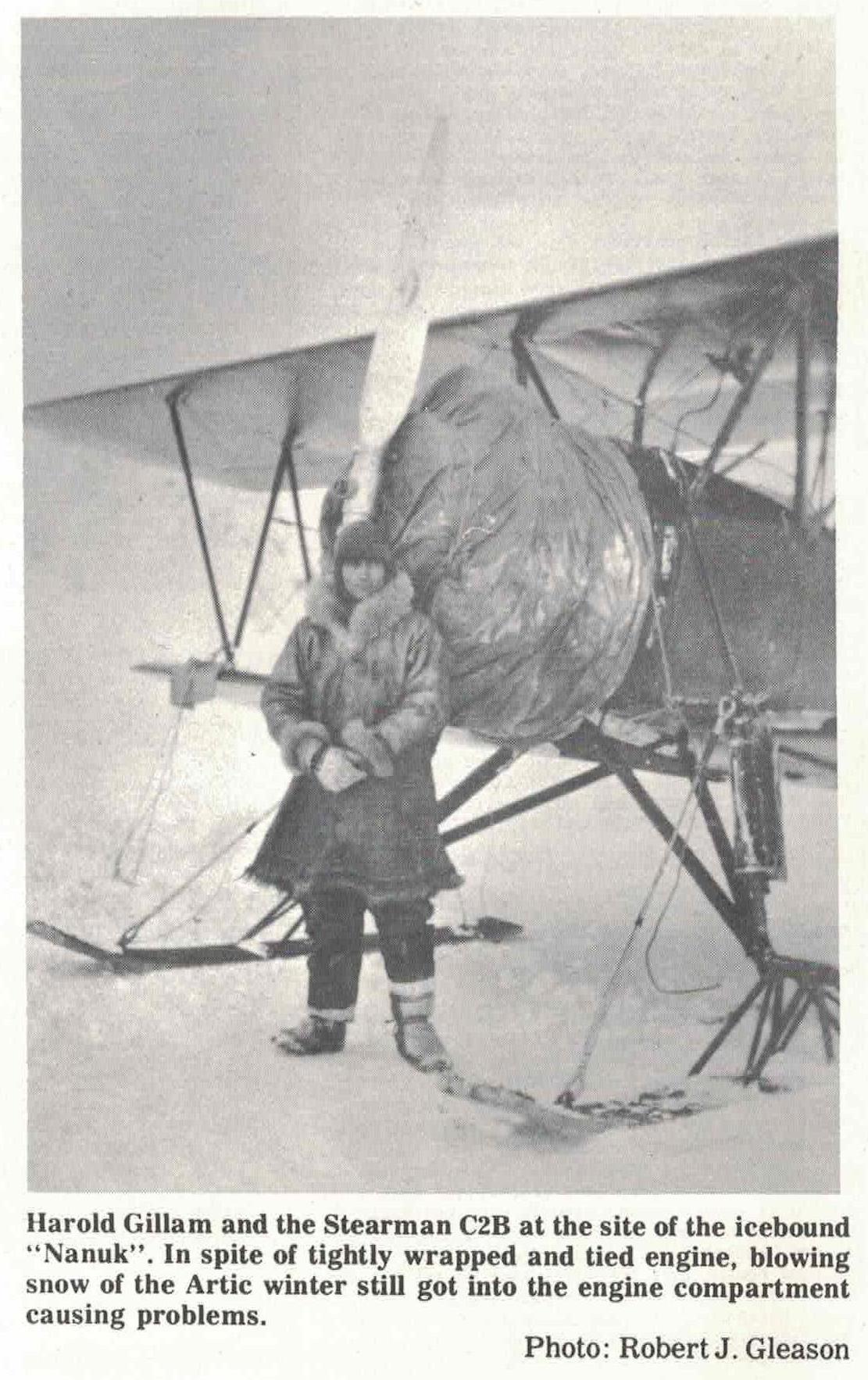

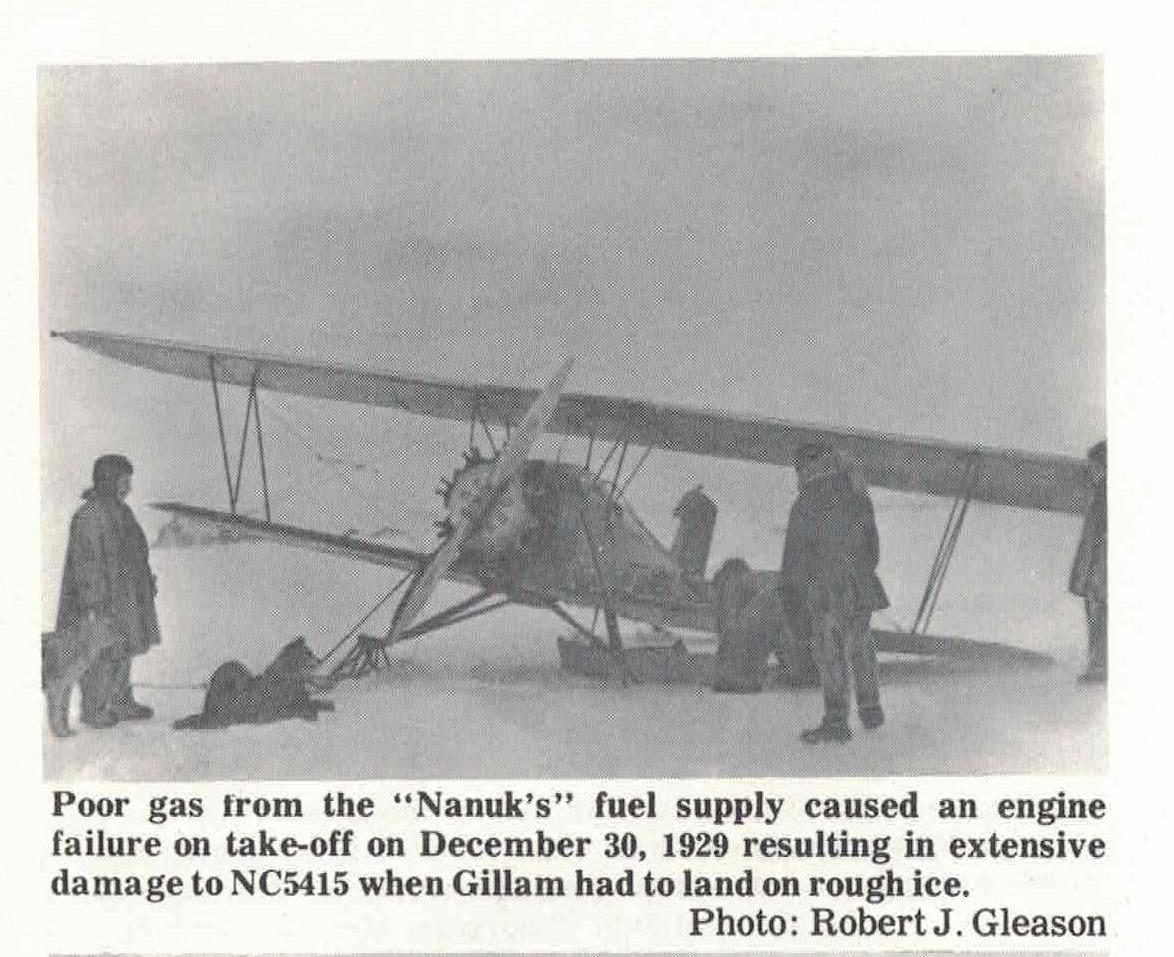

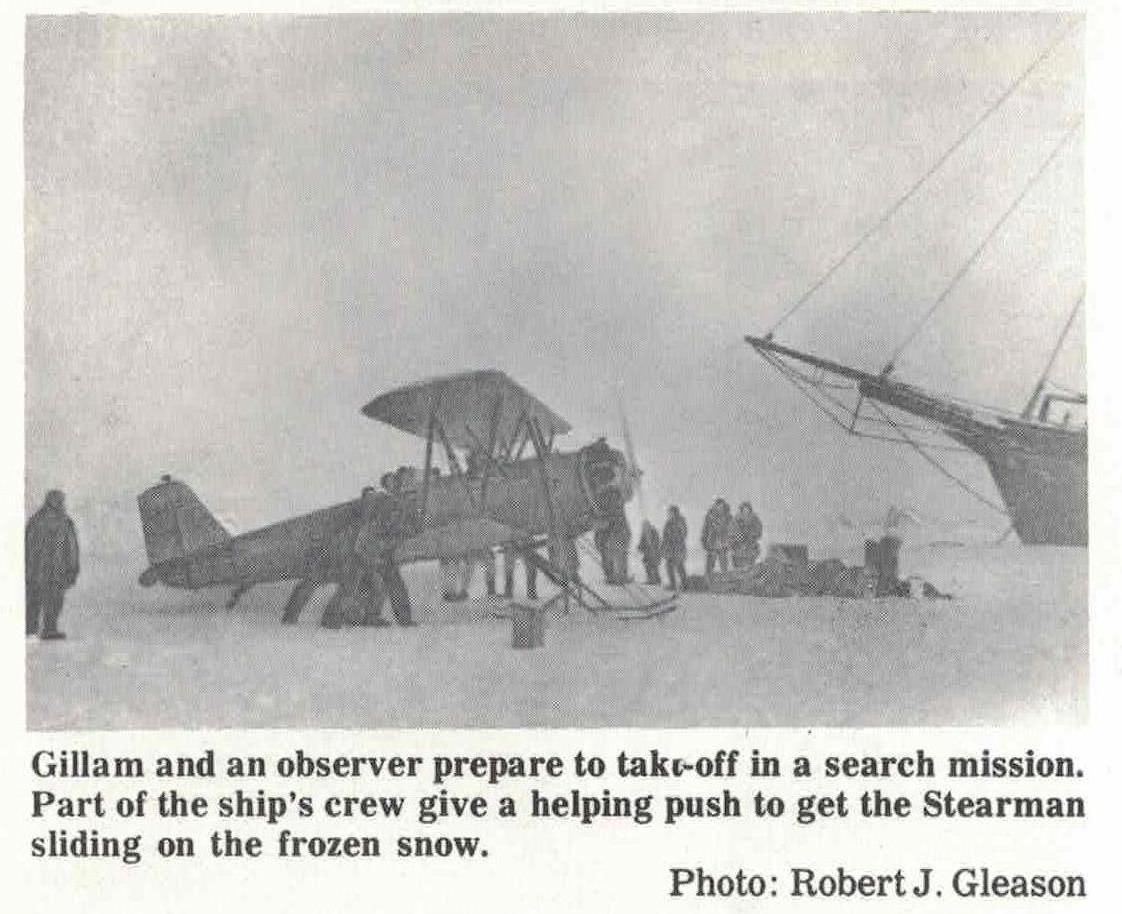

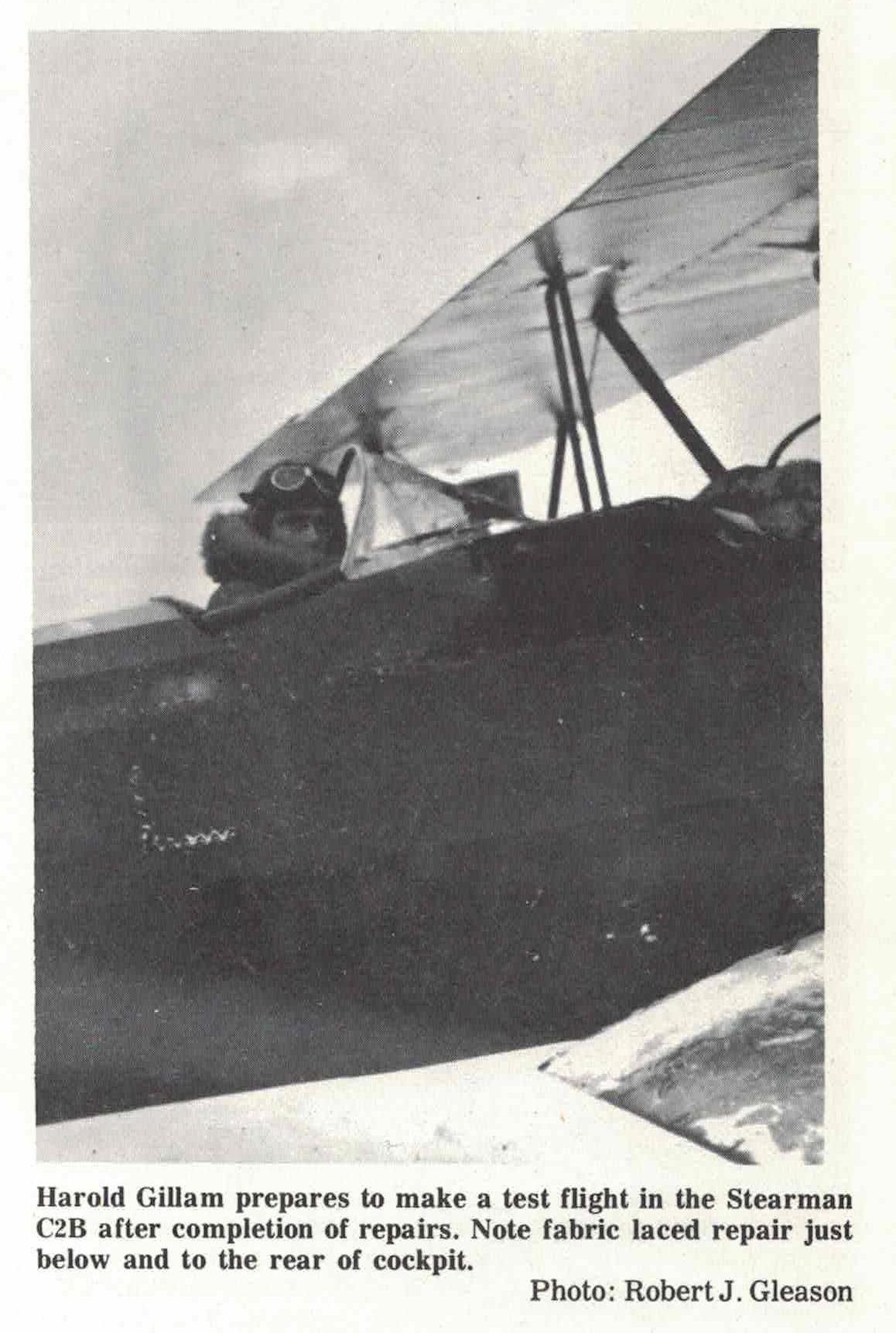

As storms would permit, over the next several weeks, both pilots, carrying observers, made several search missions but all to no avail. Of course trying to keep the airplane engines running at all under such adverse weather conditions was a constant problem, but trying to operate them on the poor grade of gas they were using from the Nanuk's supply made matters even worse. Since the temperatures were ranging far below zero, Crosson and Gillam had to resort to immediate takeoffs once the preheated engines were started and on one occasion Gillam had the Wright J4 engine on the Stearman quit on takeoff. Since he was beyond the smooth ice of the small takeoff area, he was forced to land on the rough ice and in so doing collapsed the left gear, bent struts supporting the wings, damaged the left wing and tore the fabric in various places. Since the raging storms were still keeping the other search planes grounded in Alaska, this precluded getting help so Crosson and Gillam set about repairing the broken plane. During the bitter storms, and using supplies from ships stores, they effected adequate temporary repairs, using such things as sled runners shaped to fit the straightened struts and then lashed on with rawhide. Fabric was repaired by heating dope on a stove and then applying the patch to the plane where it promptly froze in place.

Several weeks after the Hamilton disappeared, a report was brought to the Nanuk that, on the day of the disappearance, the plane had been heard flying in first a westerly and then an easterly direction which raised the possibility that Eielson and Borland may have attempted to return to Alaska. It was decided that as soon as repairs on Gillam's Stearman were finished, he and Crosson would fly down the coast to the native villages and attempt to verify the report and if it proved true the pilots would continue on to Alaska and resume the search there. Repairs on the Stearman were finished on Jan. 20, and a cautious test flight by Gillam proved the ship airworthy, so it was agreed that the pilots would start down the coast the following day, weather permitting. storms continued for several days, but finally on the 26th the weather broke clear with even a low sun in the sky. The pair took off by 9:30 in the morning and the crew of the Nanuk returned to their normal duties. They were surprised when the two planes returned shortly after noon and assumed that the pilots had been turned back by weather until they taxied up and Crosson told them that the search was over. They had found the wreckage 10 miles inland and almost 100 miles southeast of the Nanuk. He related how, because of the clear weather, they had flown further inland than any time previously, and investigating a strange shadow cast by the low sun had discovered the wing of the Hamilton protruding from the snow both Gillam and Crosson landed on the rough snow packed tundra and searched the wreckage to try and uncover the tragic fate of Eielson and Borland. The twisted and torn metal of the Hamilton indicated that they must have been killed instantly, since the plane had disintegrated on impact, but their bodies were not in the wreckage nor near the crash site. In the short time the pair could stay, they could only ponder the tragic circumstances and guess where the bodies might be, they were apparently somewhere under the recent deep hard packed snow, since there was no evidence that the wreckage had been disturbed.

Not until several days after the wreckage was discovered did the enclosed cabin Fairchilds (from Alaska and Canada) and the Russian Junkers arrive, but even then Gillam continued in the Stearman, making almost daily trips to the wreckage site hauling personnel and supplies until Eielson and Borland were found in mid February. Their bodies had been thrown hundreds of feet from the crash site and had become buried under the deep frozen snow. Even then, Gillam and Stearman NC5415 continued the flights, bringing back personnel and equipment until early March. Four months after the beginning of their fateful flight, the bodies of Eielson and Borland were returned to Fairbanks aboard a cabin type Fairchild, arriving on March 10, 1930. Stearman NC5415, flown by a now seasoned Alaskan pilot, Harold Gillam, accompanied the sad flight. The whole episode had been a tragic waste, two lives and an aircraft had been lost, several planes had been damaged, and few furs had been removed.

After the Siberian adventure the planes of Alaskan Airways returned to more mundane chores, but all was not work as I found out during my search for information. I had never met Lillian Crosson, but after coming into possession of the Stearman remains I called her and after explaining the purpose of my call got a long silence. I wondered if I had said something wrong, but then she said "Do you mean you have that old Stearman and are going to rebuild it? Why, that's the plane Joe and I used when we got married". They had flown to a neighboring town for the ceremony. Jerry Jones, who I have met and correspond with, told me how he and others used the Stearman for occasional fishing trips, and then there's the story that Crosson and Wiley Post used the Stearman for a hunting trip around the area.

In spite of poor landing conditions at many locations, Stearman C2B was used to haul medical and other supplies to remote Eskimo villages or miners to their diggings. Jerry in a recent letter says that in looking back, he now realizes that because of the excellent handling characteristics of the Stearman, the pilots, back then, were using the ship for jobs that in modern aviation would be done by helicopter. Sometime during that period a later model Wright J5 engine was installed, replacing the original Wright J4, The J5 increased both reliability and performance.

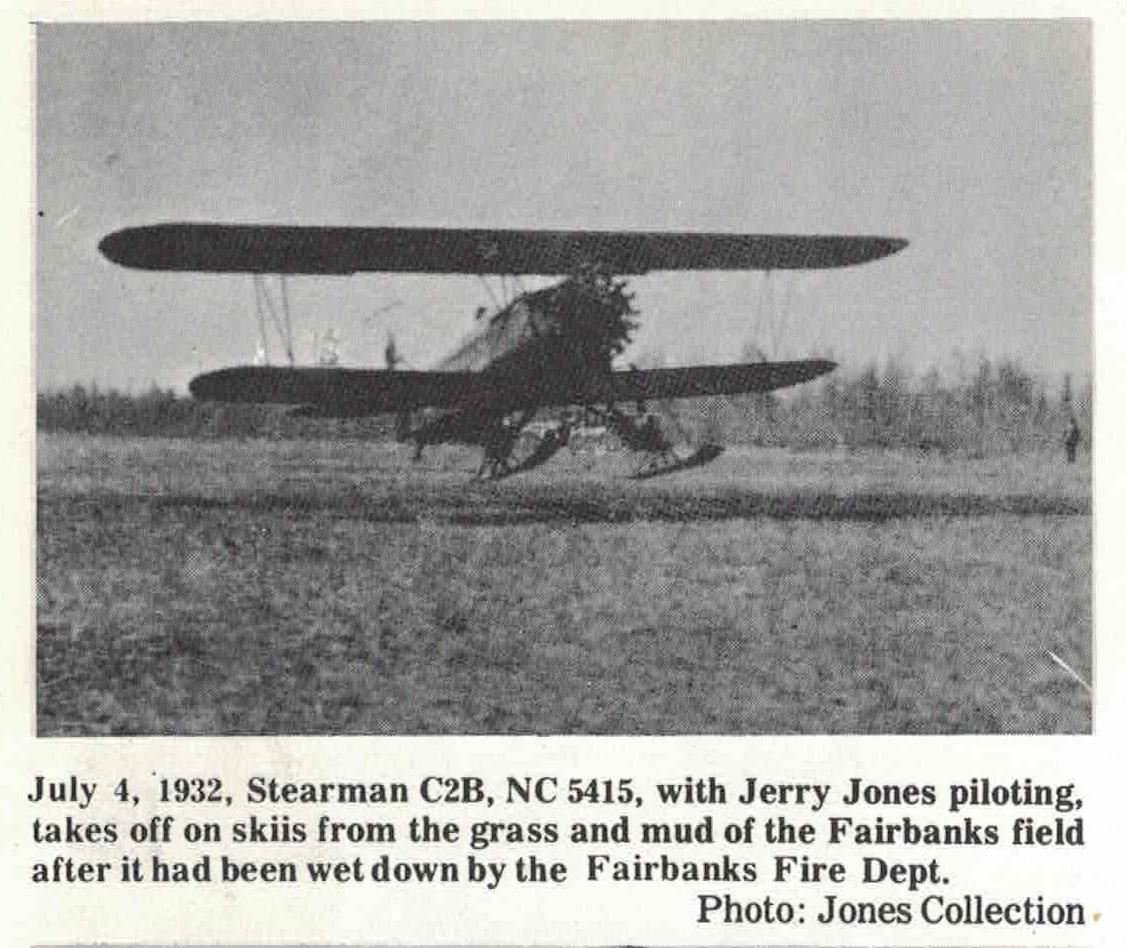

Jerry also related another most interesting episode that took place in 1932. A scientific party, the Carpe-Koven Cosmic Ray Measurement Expedition, interested in doing research in cosmic radiation, a phenomenon, then but little understood, wanted to attain the heights of Mt. McKinley. They wished to avoid as much climbing as possible so contacted Joe Crosson about the prospects of being flown up to Muldrow Glacier. This would require a plane fitted with skiis to make the landing, but a glacier landing had never been attempted before. Joe accepted the challenge and chose a Fairchild as the main ship, but also wanted the Stearman along because, as Jerry wrote, they felt that if anything went wrong they could depend on the old Stearman to get them off the high slope. It was late spring and the field at Fairbanks was snow free, so still frozen Harding Lake south of Fairbanks was chosen as the takeoff point. Taking off from Fairbanks, the wheel equipped planes were landed on the lake ice where they were refitted with skiis for the trip to the glacier. After arriving over Muldrow and carefully examining the proposed landing area, Crosson in the Fairchild, and Jerry Jones in the Stearman set down with little difficulty, giving no thought to the fact that they had made the first glacier landings in aviation history.

As midsummer arrived, word was received in Fairbanks that tragedy had struck the climbing party. Mr. Carpe had fallen into a cravasse, never to be found, and Mr. Koven had died of exposure after suffering serious injury from a near fall into a cravasse. The message also related that another member of the party, Edward Beckwith (in his sixties), was dying of Mountain Pheumonia and would need rescue by plane to save his life. Jerry Jones and the Stearman, were selected for the rescue, but at that time of year there was no snow available for a ski takeoff in or near Fairbanks, but skis would be necessary for the glacier landing. Jones solved this problem by having the Fairbanks Fire Department come out and wet down the dirt and grass on the airstrip and while this was being done, the wheels were exchanged for winter skiis on the Stearman. Sliding over the few hundred feet of slippery mud, Jerry coaxed the plane into the air and headed for his rendezvous with the ailing climber on the glacier. Other than the usual sloppy weather, as Jerry called it, he experienced little difficulty on his hazardous rescue trip. Landing at the base camp, he picked up Beckwith and returned to Fairbanks, where he again utilized the muddy field to execute his landing. Beckwith completely recovered red from his ordeal and later wrote a book on his Mt. McKinley expedition experience.

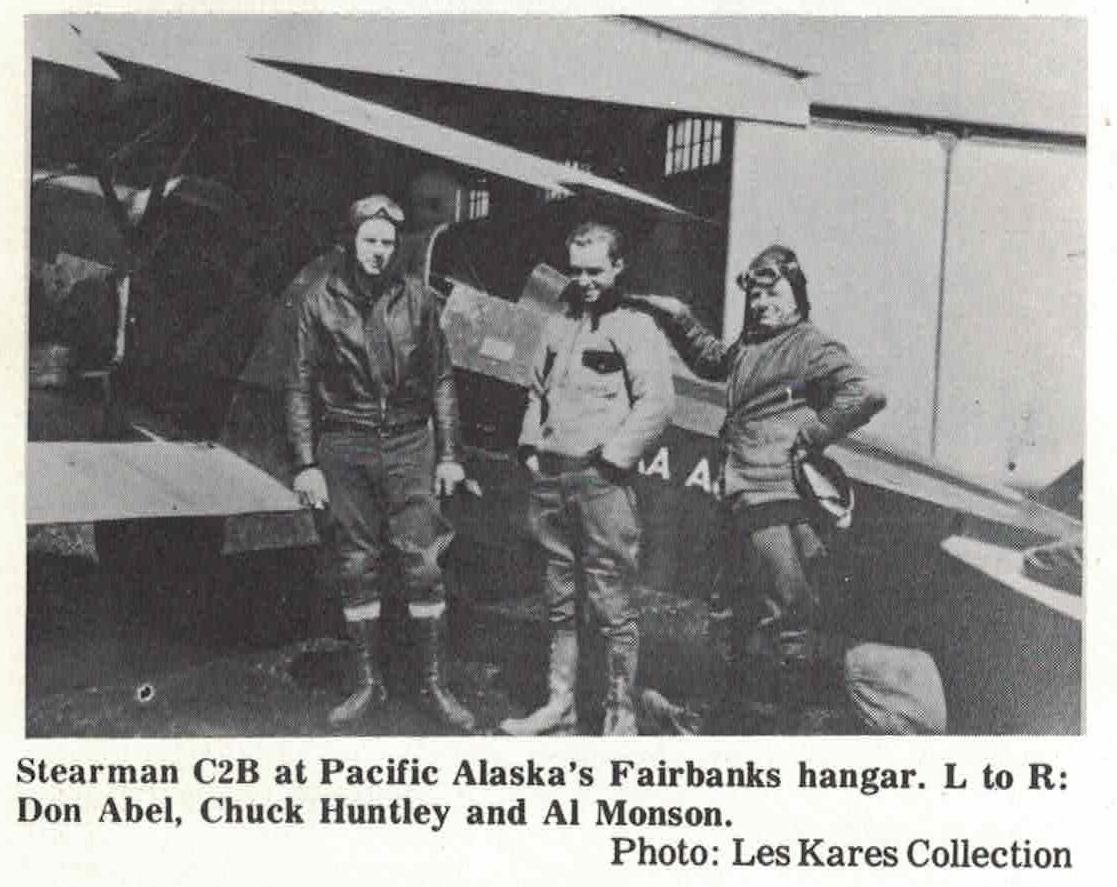

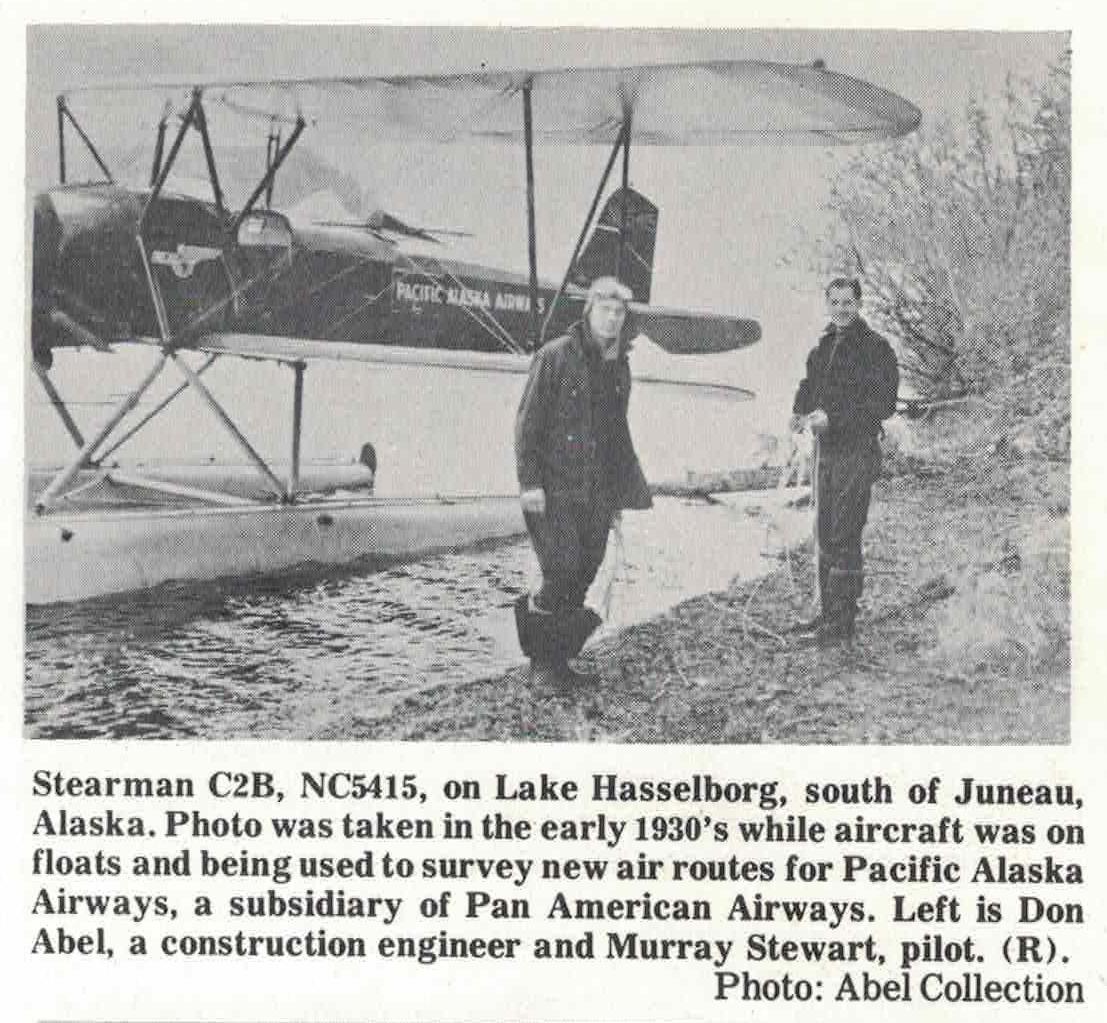

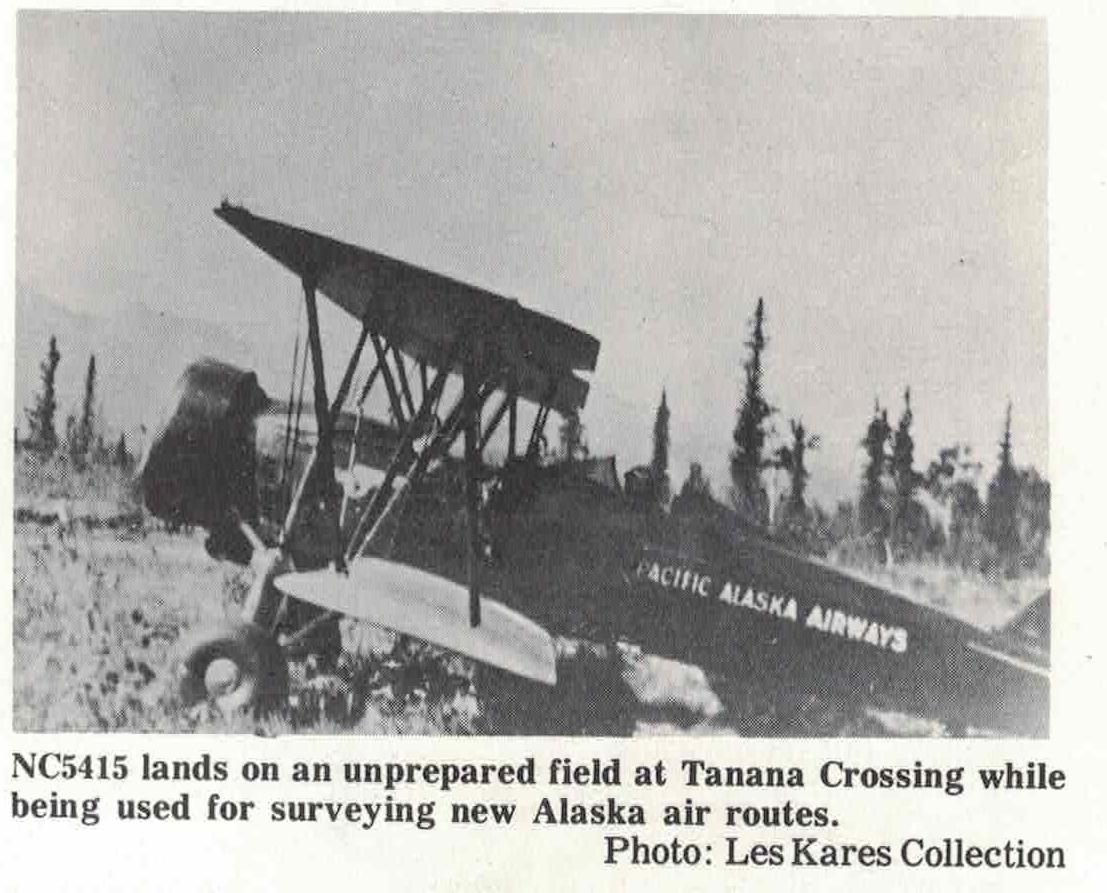

As newer and better aircraft became available, the Stearman was shuffled into odd jobs where it's small cargo capacity was not as important as its ability to operate out of small unimproved strips. Pan American took over the Alaskan Airlines operation and renamed it Pacific Alaska Airlines and for a while used the Stearman to survey possible new routes as well as set up new communication stations around the area. Bob Gleason, after his Siberian adventure at North Cape, in Siberia, joined Pacific Alaska and related, in a letter, how he had made many trips in the old Stearman in his capacity of establishing these communication stations. It is interesting to note that while the Stearman was operated by Alaskan Airways, the ship carried the "AA" logo of the parent company, American Airways (now American Airlines) and after Pacific Alaska assumed control, the ship carried the winged world "PAA" logo of Pan American Airways.

I was never able to ascertain when Pacific Alaska disposed of Stearman C2B, or the chain of ownership after that, but apparently the ship was shuffled around to several places doing the odd jobs of the small operators, finally ending up with Cordova Air Service, based at Cordova, Alaska.

It wasn't until the mid thirties that the Federal Government seriously started getting involved in regulating aviation; and aircraft in particular, and in the remote areas of Alaska, record filing was intermittent at best until the Civil Aeronautics Authority was signed into law in mid 1938. I was delighted when Mr. Dick Brodowy of the Helena, Montana FAA office told me that he was having the Oklahoma office research their files, and he later presented me with copies of a number of old inspection and repair forms that Cordova Air Service had submitted, starting in 1938. From the records, it appears that the Stearman spent more time being repaired, after damaging accidents, than anything else, but in between repairs it was used to fly mail and supplies to the many small mining camps in the surrounding area. The last inspection form (to relicense the ship after an accident the previous month) is dated. August 1, 1939, and it was apparently shortly. after that when Stearman NC5415 made its last fateful flight in Alaska. Who the pilot was, I have never been able to determine for sure, since as mentioned in the beginning of this narrative, the pioneer aviation people who would know the precise facts have never responded to inquiries, but the important fact is, that while out on yet another trip over rugged terrain and after experiencing engine failure, the ship force landed on a mountain so remote remote and inaccessible that it was not feasible, particularly with the means available at that time, to attempt to bring the damaged plane out.

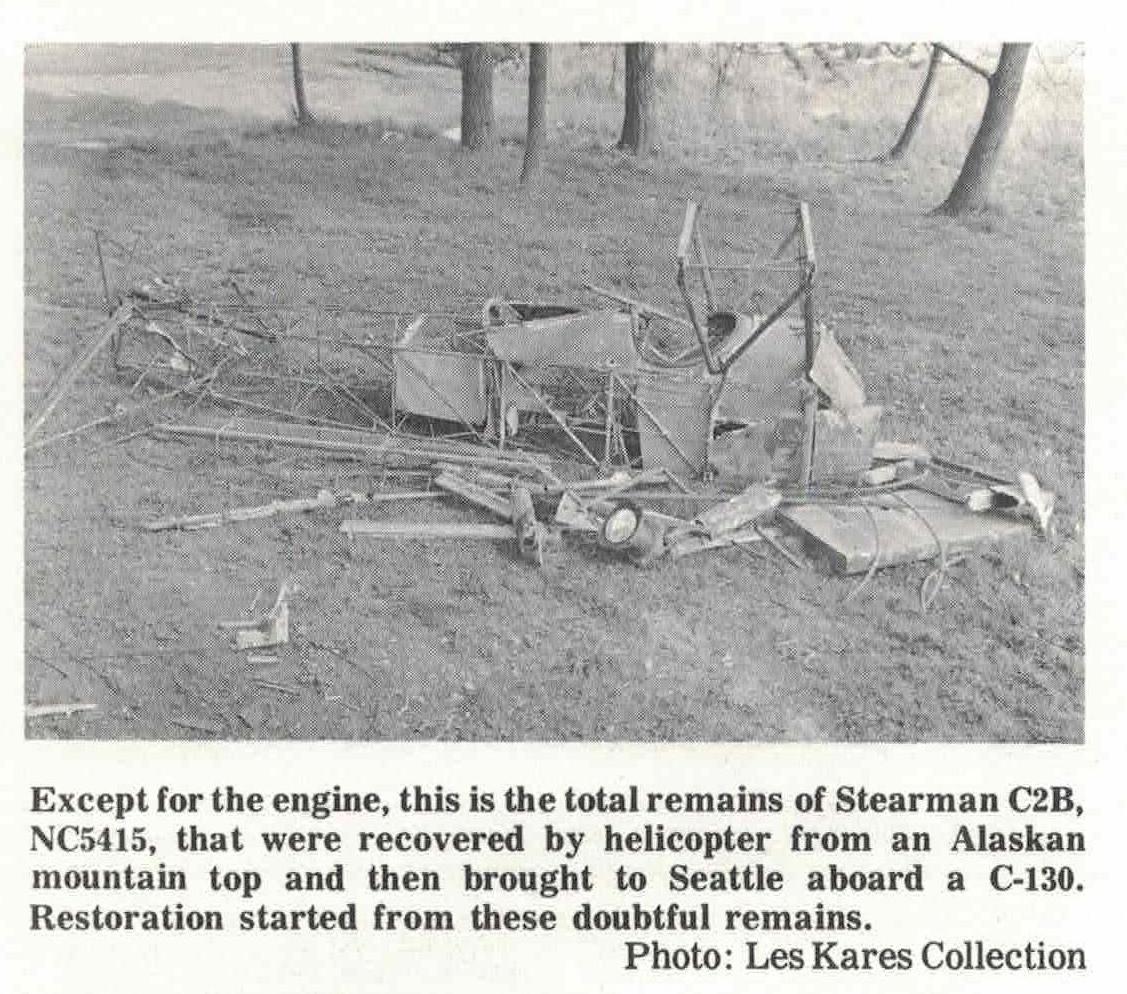

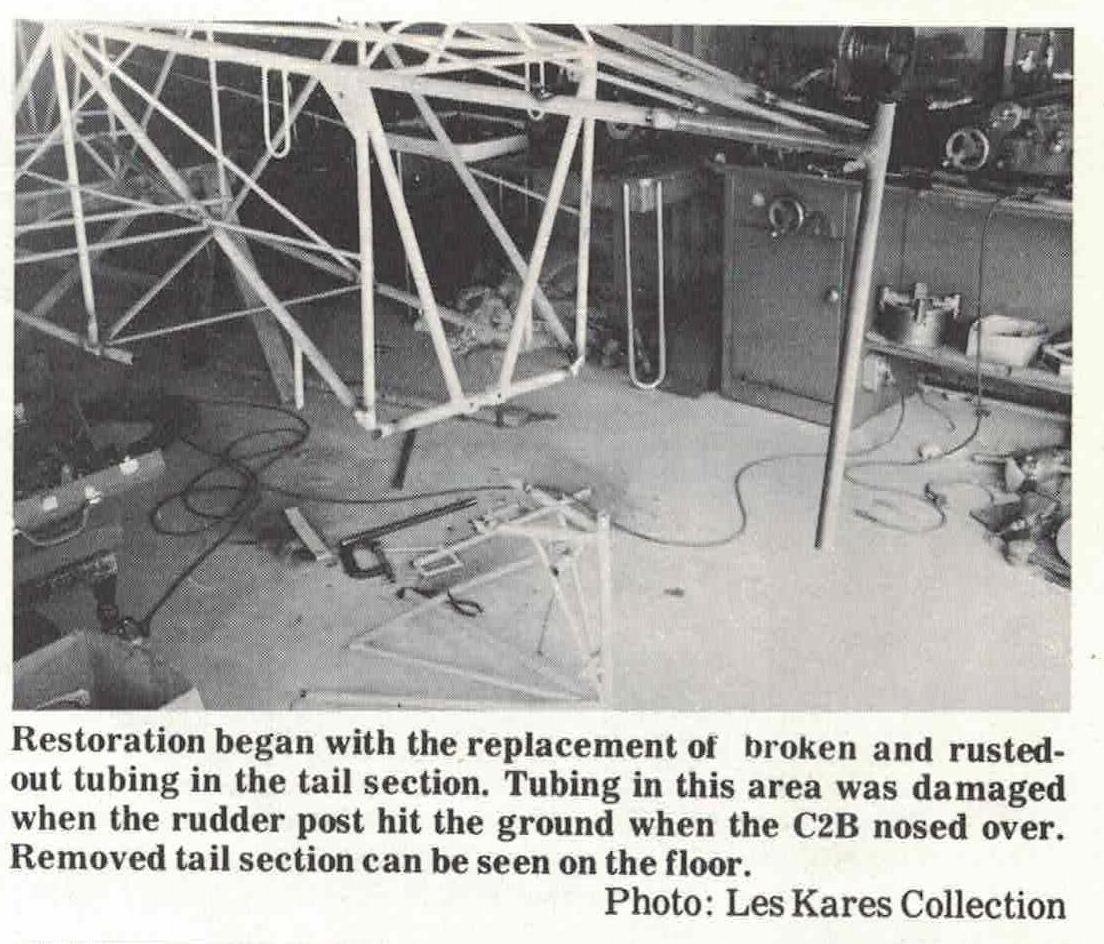

At the time of the accident the ship was equipped with wheels, making a landing on rough terrain or snow difficult, and from the wreckage acquired it was quite obvious that the ship traveled but a short distance before the left landing gear struck something, collapsed and the plane rolled on its back. The propeller had apparently stopped in a vertical position as the ship nosed over, it bent the propeller blades over the engine, damaging parts of the engine and damaging the engine mount. The rudder post alto struck the ground, bending and breaking the steel tubing in that area of the tail, indicating the ship must have rolled over with considerable force. After the crash, probably for salvage reasons, the wing spars had been chopped through and flying wires cut, presumably to roll the fuselage over to remove anything of value that could be packed out (the entire instrument panel was missing). It was an inglorious ending indeed, for a once proud flying machine, to be forsaken, it seemed, forevermore.

Stearman C2B laid for almost thirty years on its glacier graveyard, slowly disintegrating and as the upper fuel tank rusted away, the small rodents pulled podding from the leather around the cockpit cowlings and quite artfully stuffed it into sections of the tank. I noted this during restoration and realized of course that it made the tank quite useless since all of the residue could never be removed. The brass and aluminum data plates were still on the plane when it crashed and it appeared from holes in the cowling that an occasional hunter had taken aim on the plates, fortunately missing each time. As mentioned earlier, wood in the wings was well decayed, but the dry climate at that altitude caused a surprisingly small amount of rust on the steel tubing of the fuselage, except where it had been broken. Since publication of the story in the Alaska Magazine, it has been brought to the attention of the authors that it was In the mid sixties that the Stearman's engine was airlifted out of the mountains and two more years went by before a helicopter was available to bring down the remainder of the ship.

The wreckage was just west of Mt. Wrangell and was helicoptered out to Gulkana, Alaska where it remained for some time before finally being transported to Seattle. Unfortunately no pictures were taken by the recovery crew on either of the two trips.

By the mid sixties, interest had grown in the restoration of antique aircraft, and so it was that in 1967 an antique buff in Seattle, after learning about the old Stearman, decided to have it rescued from the mountain. Due to its inaccessability, a helicopter was the only means that could be used for recovery. I'm sure that if the old ship had a spirit, it would have been taken a little aback by the apparition of the strange machine with wildly flapping wings that had come to effect the rescue. For that matter, the rescue crew was probably taken aback at the sight of the apparently useless pieces of scrap metal that they had been sent to pick up. It didn't appear that it could be of any value to anyone. I will have to say however that the rescue crew must have used a broom cleaning it up because every little scrap that would be of value in the restoration was returned.

After a forty year career of the best and the worst, in Alaskan pioneer aviation, Stearman NC5415, finally returned to Seattle in early 1968 with the hopes of a brighter future, only to shortly have a setback when the plane's would be savior abandoned the project after the lowest bid for rebuilding was prohibitively high (this antique buff was not a rebuilder himself, but rather a collector). The remains were then given to a local aircraft mechanic school with same thought that they might have the students rebuilt it, but such schools of today have little time or use for such projects. The school was also told they could do anything they wanted with it, and the decision came quickly. Let the students cut up the steel tubing and use it for welding practice. Fortunately, one of the older instructors felt there might be someone interested in restoring the ship. One person it was offered to, knew I was looking for a project so contacted me and I reluctantly accepted. It should be pointed out again that all data plates had previously been removed by someone unknown when the plane first reached Seattle. It was difficult to determine the make of the plane or even guess of its illustrious history. I later found out who had the main name plate showing make, model, and other details, and also discovered that the other two plates had been removed by overzealous mechanics while the plane was stored in a hangar. With much perseverance and some luck, I eventually managed to get them all back and the information on these plates opened the door to the ship's past history. It still took many months before I could convince myself that the project was worth starting.

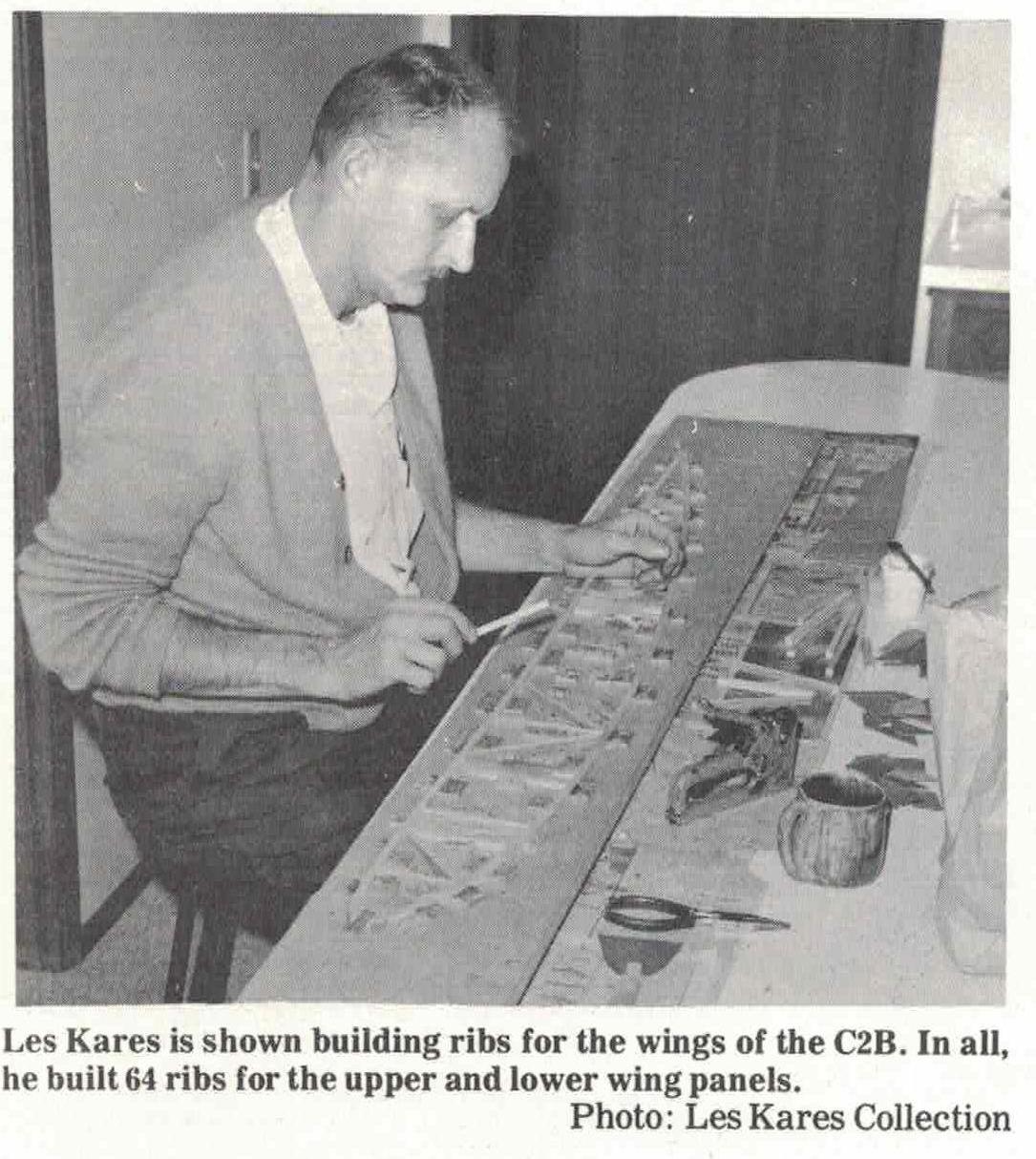

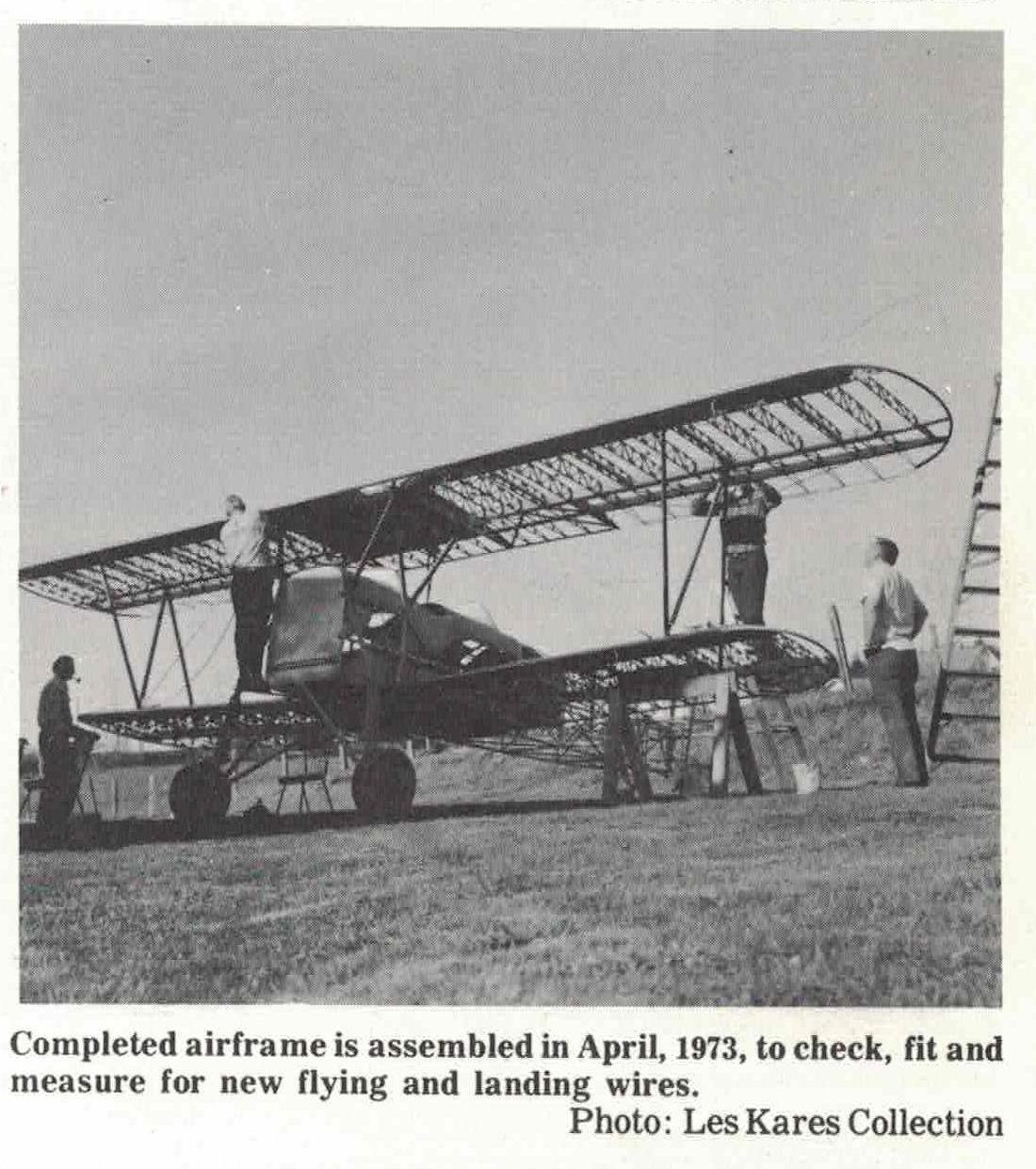

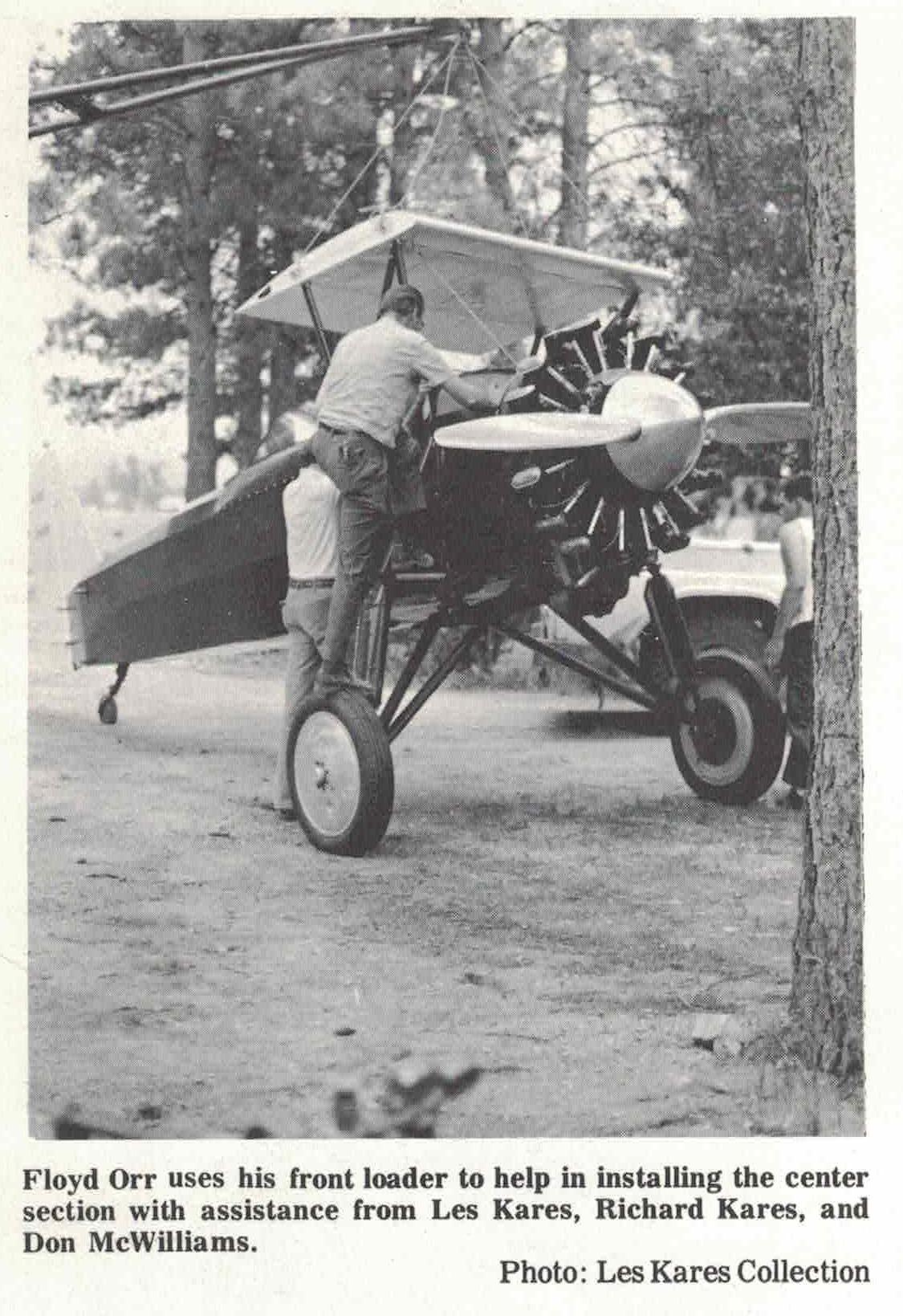

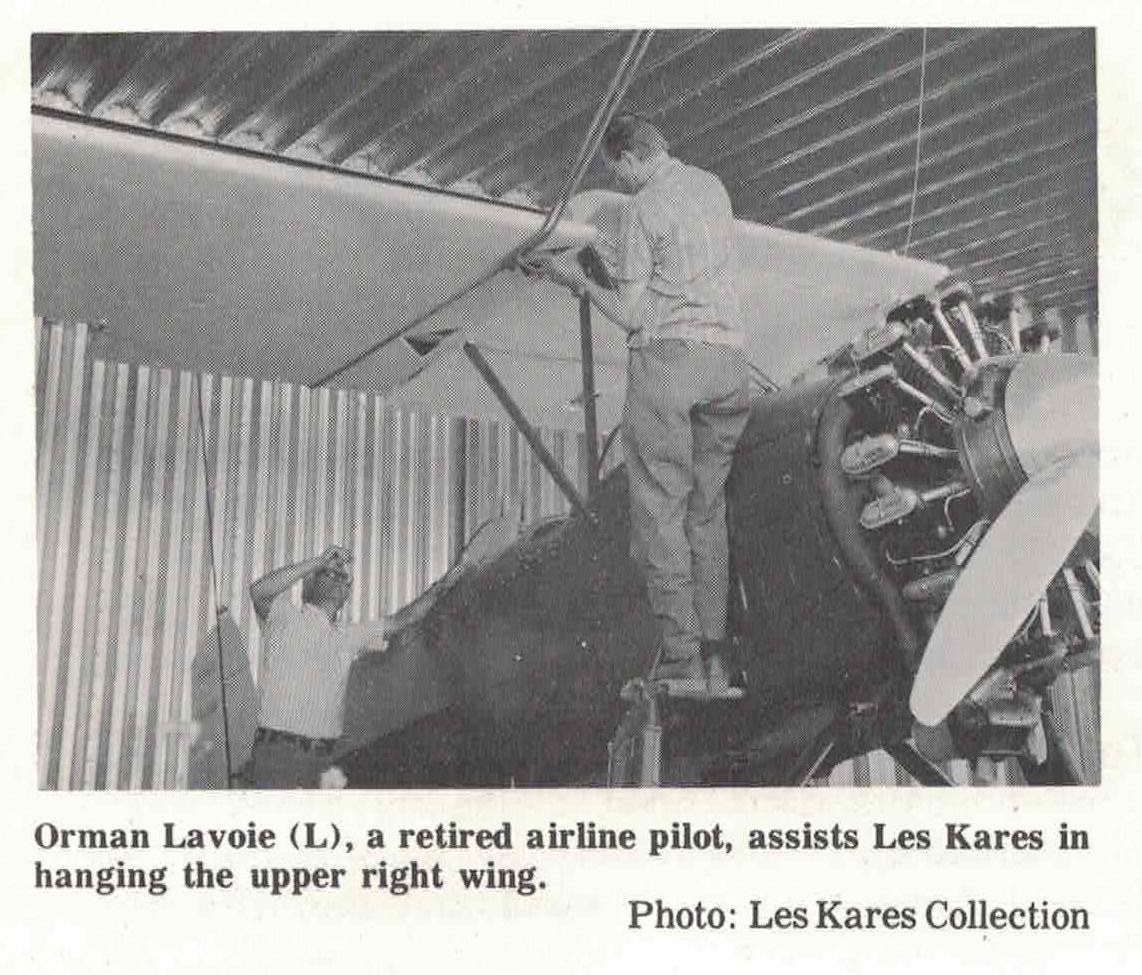

After finally getting the fuselage stripped down and having it sandblasted the project looked better, but it was obviously going to be a long and patient job. After painting with rust inhibiting chromate, the fuselage frame was kept under cover (probably for the first time since the ship was built). The project finally got underway with the welding in of new steel tubing where the original was bent and broken. New steel tubing tail surfaces also had to be fabricated, after which the more general work involved with any restoration progressed. Luckily, just enough remained of, all the original steel and wood structures (including spars and wing ribs) for adequate patterns. Broken wings were often repaired or replaced on old aircraft during their lifetime of use, and although I also had to build new wings, what I think important is that on this ship, after restoration was complete, the fuselage remained virtually original. It still carries the same control stick, rudder and brake pedals, etc. that Wien, Gillam, Crosson and the other pilots, of the time, used to operate the plane. By the same token, in some places, there remain the welds that Jim Hutchinson and other pioneer mechanics made while making early day repairs. Indeed, all through the restoration process every effort was made to retain as much as possible of the original (within the bounds of safety), down to the smallest fittings. Although requiring a considerable amount of patching and straightening, the original cockpit cowlings were utilized, however, engine fairings were so badly bent and torn that it was necessary to fabricate new pieces. I wanted the finished ship to look much as it had when first arriving in Alaska, so I also turned out a new aluminum propeller spinner, although one was not used on the ship in Alaska after the original was damaged in the plane's first accident on Walker Lake. A propeller spinner adds a lot to the looks of the Stearman, but actually, by not using one it made maintenance of the engine much easier, which was of prime importance to the early pilots and mechanics of the day. To make some of the new parts for both plane and engine, I had to manufacture special tools which usually took longer to make than the new parts.

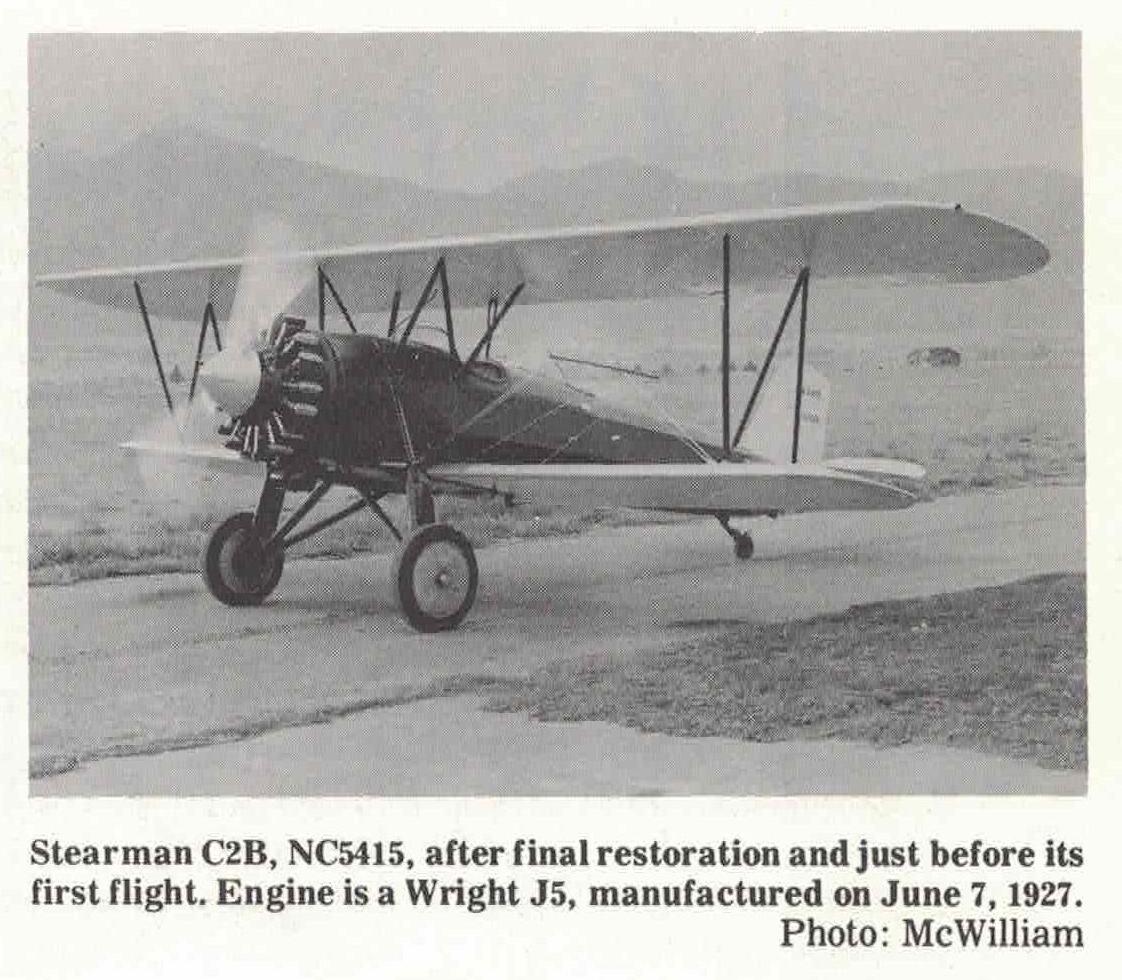

The old Wright J5 engine that came off the mountain with the airframe was a prize that perhaps only a genuine old antique buff could appreciate. This powerplant in its day was considered one of the finest and most reliable of its time, as attest to the fact that Lindbergh had the exact duplicate on his Spirit of St. Louis when he spanned the Atlantic in late May of 1927. In fact, this engine was manufactured on June 8, 1927, little more than a week after he made his famous flight.

Considering the date of manufacture, the close tolerances these engines were manufactured to, has always been a source of amazement to me. This one was reported to have been given a major overhaul shortly before the final flight, but if that was the case, someone didn't bother to check the tolerances, because when I overhauled it I had to spend hours turning out all new bronze sleeve bearings to replace the worn ones, where required, between all moving surfaces. For all the years the engine laid out on the mountain it was in surprisingly good condition. When I first disassembled it, I was delighted to find all the gears and other moving parts inside as bright and shiny as the day it came out of the factory. It did appear however that the last overhaul had been done in a rather casual manner. The old mild-steel exhaust stack had rusted through over the years which in turn let moisture run down through open valves causing slight rust in three cylinders, and although I could have used them, with proper and expensive repair, I kept searching until I found three replacements. That is the biggest problem in trying to overhaul such an old powerplant----there are so few spare parts to be found at any price. I did have one pleasant surprise however, when I got enough courage to see about replacing the three large ball bearings supporting the crankshaft. I could see nothing but trouble in trying to get bearings that would fit, and could hardly believe it when the clerk took the numbers off the fifty year old bearings, walked over to a shelf and handed me the exact same bearings in size and other dimensions, but many times better in structural strength. They would be the only shelf items I would find.

Some structural damage had occurred to aluminum castings both in and outside of the engine, which required the work of a certified welder and then machining. Pistons were cleaned and checked for cracks, new piston rings custom made, valves ground and reseated and other usual engine overhaul work done. Even the original mica spark plugs were usable after proper cleaning, and to give spark to the plugs, the old Scintilla magnetos were cleaned and oiled. It's interesting that, after being exposed to the heat and cold of thirty years, the magnetos still retained their spark, which I shockingly learned the first time I gave the shaft on one of them a spin. A bench check confirmed that the magnets would not have to be remagnetized. The propeller had to be overhauled and the hub replated and to finish it all off, I spent weeks welding up an all stainless steel exhaust stack to the contour and size of the original. I think that the single biggest thrill during the entire restoration was when I started the reassembled engine. No one quite knew the proper starting sequence, but something was apparently done right, because, after a helper started cranking the old direct drive starter, the propeller turned about half a revolution and the 51 year old engine barked to life. It ran so perfectly that it has not been adjusted in any way since.

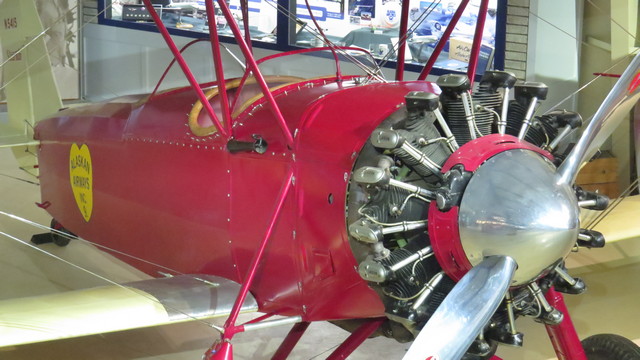

Although it raised the eyebrows of some dedicated old timers, I nevertheless used the more modern dacron fabric to recover the entire airframe instead of the traditional cotton, once used on all fabric ships. I feel that dacron produces a better finished look, and it becomes an almost permanent covering. After what the Stearman had gone through, it deserved something more permanent. The ship was finished with cream colored wings and tail surfaces that contrasts with the deep red of the fuselage. Riveting the original brass data (nameplate) back on the cowling near the rear cockpit was the final touch. These plates seldom stayed on a ship over the years, either being left off after paint jobs, or pocketed by some collector, so I felt most fortunate that this one was on the plane when it was abandoned. This plate engenders some nostalgia because it shows the wear caused by the many pilots dragging their leg over it as they climbed into the rear cockpit.

Early stages of restoration were done while living near Seattle, but in 1976 I moved back to my home town of Stevensville, Montana, located just south of Missoula. Last stages of restoration were done here and final assembly took place on the small outlying field. From all the flattering comments, I'm sure the old Stearman thought it was really something special, which of course it is, Naturally I was pleased too, to see it a complete airplane again after the years of work and especially to see it carrying its original registration number. After the ship had been wrecked and abandoned, it was stricken from the federal records and its registration number assigned to other aircraft over the years. I finally traced the number to a crop dusting Ag Cat in Mississippi, contacted the owner, and he graciously agreed to let me have it, and got a new number for his ship.

When the Stearman met its fate in 1939, aircraft were not yet issued Permanent Airworthiness Certificates, but instead had to be issued a new one each year. In later years the FAA began the issuance of Permanent Certificates, and requiring annual inspections for relicensing. Since the Stearman had never been given the Permanent. Airworthiness Certificate (which can be only issued by an FAA inspector) that was the last hurdle I had to overcome to make the ship legally airworthy. On September 27, 1978, 50 years and 6 months after the plane was originally built, Mr. Dick Brodowy of the Helena, Montana Office of the FAA, made the required inspection and handed me the coveted certificate. Except for test flight, the job was complete. The Stearman's first flight in almost 40 years was somewhat anticlimatic, being done primarily to prove that the ship was indeed airworthy. Flying characteristics were excellent, and the plane required no rerigging of any kind.

In looking back, I realize the whole project was one of patience and perseverance, tinged with a little curiosity as to the outcome, but not a project that I would care to undertake again. I became interested in aviation at an early age, after witnessing events like the Ford Reliability Tour when it came to Davenport, Iowa, where I lived as a child, in 1928. Over the years, along with other flying stories, I recall reading the accounts of the Alaskan Bush Pilots, but gave little thought at the time to the possibility that I would ever meet any of them. Many years later then, while still in Seattle, it was a pleasure to meet pioneers like Noel Wien, Murrell Sassen, Shell Simmons, Gordon Graham (originally from Missoula, Montana), Jerry Jones, Lloyd Jarman and others and hear their reminiscences, especially when some of them came to my home to look at the Stearman during its rebuilding.

It is a real possibility that none of this would have come to pass if I had not had the undying support of my wife Janet, who gave encouragement, occasional prodding, sometimes physical labor, and ran impossible errands for supplies and who trusted the finished product enough to ride as the first passenger.

Stearman C2B NC5415 is one of the original aircraft that helped open up Alaska's vast interior and was owned and flown by some of the most renowned of Alaskan pioneer Bush Pilots. I have always felt that Alaskans held a special pride for these early planes and pilots and so it would seem only fitting that this remaining historic aircraft should be given a rightful place of honor in a display of Alaskan Aviation History. In such a setting, the young could always see the frail beginnings, and perhaps it might be remembered by some of the oldsters from Fairbanks, or Nome, or perhaps even from other bustling fields it flew to like Unalakleet...or Chalkyitsik ... Napaskiak ... Kaltag ... Valdez ... Koyuk ... Kotzebue ... Shismareff. ...

This article originally was published, in an edited form, in Alaska magazine, December 1980 Volume XLVI/No. 12. We thank Alaska magazine for permission to reprint this material and to Les Kares for providing the entire original manuscript and photos.